Climate change brings water concerns

YOSEMITE VALLEY, Calif.—The biggest attraction for individuals staying at the Yosemite Lodge of Yosemite National Park is that when you wake up in the morning and open the door, Yosemite Falls come into view pouring down the granite cliff behind the golden-colored leaves of this fall season.

But when you appreciate that nature has endowed us with such splendor, have you ever imagined the risk of losing it all one day?

“Climate change is happening,” a National Park Service brochure distributed at the Yosemite Visitor Center tells park guests.

“Climate change and global warming is not only a scientific reality, but also truly affecting the beauties, landscapes, and inhabitants of our park,” said Yenyen Chan, a Yosemite National Park ranger of Interpretation and Education.

“It could have impact on this tiny animal,” Chan said, putting a little cute toy pika on the table. Every time she was talking about the impact of climate change at the park’s interpretation programs, she would bring it.

Pikas, a relative of the rabbit, were recorded living in the Yosemite National Park as low as 7,500 feet in the early 20th century, but scientists today cannot find pikas below 9,500 feet, according to the report “Losing Ground” published by the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization and Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in 2006.

| At right, the Lower Yosemite Falls in October (Photo by Dongran Sun). Next below, Yosemite National Park in winter (Photo courtesy of National Park Service). Next, Mirror Lake (Photo by Dongran Sun). Next, Yenyen Chan, Yosemite park ranger, talks frequently about climate change, showing the tiny pika. Sentinel Meadow with part of Upper Yosemite Falls visible in the clouds during 2005 flood (Photo courtesy of National Park Service). |

“The warming temperatures are forcing pikas to climb higher in search of alpine conditions. They are thriving for snows that do not melt fast in Tuolumne Meadows,” Chan said.

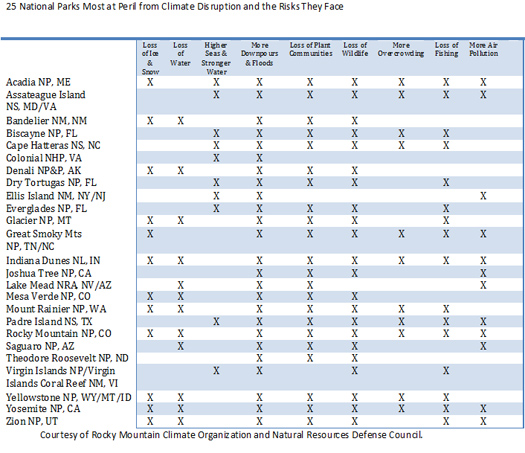

The two organizations’ 2009 report “National Parks in Peril: the Threats of Climate Disruption” released in October indicates that Yosemite National Park is among the 25 national parks most at peril from climate disruption. (An excerpt from a table from the report is presented below, at the end of this story.)

The risks it faces include loss of ice and snow, loss of water, more downpours and floods, loss of plant communities, loss of wildlife, more overcrowding, loss of fishing, and more air pollution.

Climate change has been an issue widely discussed during the previous 20 years and is the most urgent threat facing humanity today. Its manifestations permeate every aspects of human life, most distinctly on water-related issues.

Climate change has been an issue widely discussed during the previous 20 years and is the most urgent threat facing humanity today. Its manifestations permeate every aspects of human life, most distinctly on water-related issues.

Mount Maclure and Mount Lyell are the two glaciers within the national park mountain range. Both were formed from Little Ice Age, less than 700 years old, and are shrinking in size.

According to recent research by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of California-San Diego, Lyell Glacier has lost 35 percent of its west lobe and 70 percent of its east lobe, mostly since 1944.

The Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier on the Sierra’s west slope, but now only 0.25 mile long from top to bottom.

“It is melting at a rate that makes it very easy to see it shrink from year to year,” Pete Devine, a resident naturalist of Yosemite Association wrote in an email, who is frequently leading trips to Lyell Glacier.

“Our scientists are also trying to study climate change and warming in Yosemite,” Chan said.

Jim Roche, the first hydrologist of Yosemite National Park, was among one of them.

“Our water supply comes primarily from snow, but snow is thought to be an endangered resource. As climate warms, especially in the winter, we will have less snow accumulation,” said Roche, speaking in an education video for the park service.

With warmer climate, precipitation is falling as rain instead of snow. And the Sierra Nevada mountain snowpack, which provides 65 percent of California’s water, is reducing.

“Rainfall doesn’t stay long in the landscape,” Chan said. “California’s water supply relies on the snow in the northern part of the state, especially during dry seasons.”

The California Climate Change Center’s “Our Changing Climate” report asserts that decreasing snowmelt coupled with hotter climate could lead to increasing water shortage to California with a rapidly growing population.

As for Yosemite National Park, Roche’s recent research presents no better situation. With his projection by the end of the century, the snowline in the park will move up to 9,000 feet with 70 percent of land below the line, compared to 6,000 feet of the current snowline and 10 percent of land below the snowline.

Unfortunately, the warming climate also changes the pattern and season of snowmelt.

“If the change keeps on going, it means that our waterfalls may full in March, April and May and by June it may start getting smaller,” Chan said.

When the climate warm up quickly in the spring, people could expect earlier spring runoff more turbulent in growing season. The waterfalls in Yosemite could reach its peak only within a short period of time, but dries quickly for the rest of the time.

Roche’s research also pointed out that earlier snowmelt and more rainfalls results in increasing likelihood of flooding, including floods that closed Yosemite Valley in January 1997 and May 2005.

On May 17, 2005, high water levels peaked at about 11 feet, 6 inches in Yosemite Valley at about 5 p.m.

“It [earlier snowmelt] also influences the vegetation and animals in the park,” Chan said.

Studies show that snowmelt and blossoming is 10 to 20 days earlier throughout the Sierra. Earlier spring bloom affects the whole time cycles of plants which in turn affect animals that rely on them for food.

“Our ecosystem is in a delicate balance, so warmer climate affects snowpack which then will affect waterfalls, vegetations, animals…” Chan said.

Having worked in the park for 10 years, she worries that much of the beauty of the park would lose its attractiveness due to those changes.

“The park’s beauty, the waterfalls, the river, the glaciers, draws people from around the world. If the waterfalls dry for the most part of the year, which means our park may be overcrowded during the peak seasons,” she explained.

“The park’s beauty, the waterfalls, the river, the glaciers, draws people from around the world. If the waterfalls dry for the most part of the year, which means our park may be overcrowded during the peak seasons,” she explained.

The ski season would have a later start and earlier closing due to the decline of Sierra Nevada snowpack. Even though Yosemite has only a small ski area run by Delaware North Company, less snow will result in decrease of winter tourism.

To fight against climate change, Yosemite National Park is listed as one of the “Climate Friendly Parks,” which aims to provide national parks with comprehensive support to address climate change with the community.

“But the program hasn’t involved much participation yet,” Chan said. “Our new director of National Park Service puts climate change very important for all of us to start talking more about. So I think we are gearing up to try to put together more programs to educate the community.”

“Because climate change is a global issue, so wherever you are, you can start eco-friendly action to help Yosemite,” Chan said.

Comments are Closed