Oral History Project preserves jazz heritage

NEW ORLEANS — The New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park faces a challenge in preserving the musical tradition that is its namesake.

“We don’t have museum artifacts per se,” Bruce Barnes, interpretive park ranger for the park, said. “It’s important to collect the histories.”

One of Barnes’ many responsibilities includes collecting archival material for the park. As such, he contributes new content to the park’s growing Oral History Project.

The project, which started in 1998 with the help of the New Orleans Jazz Commission, seeks to collect interviews with those who were directly involved in shaping New Orleans jazz. Currently, the project contains, according to Barnes, about 173 oral histories.

An earlier effort by the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University began in 1958.

According to Bruce Raeburn, the archive’s current curator, that project began when a prospective graduate student, Richard B. Allen, mentioned the idea of oral history techniques to the chair of the Department of History, Professor William Ransom Hogan, for his study.

| At right, Benny Jones, Sr., one of the many musicians interviewed for the Jazz National Historical Park’s oral history project. (Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park). |  |

“Hogan suggested that the project might be expanded into a research collection and prepared a grant proposal to the Ford Foundation to enable systematic oral history fieldwork with early jazz pioneers—an informant group that ultimately included more than 700 individuals,” Raeburn said.

The Hogan Jazz Archive still plays a major role in the development of the oral history project at the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park.

“We collaborate on various projects,” Raeburn said. “We make images available for their exhibits, assist with editing text, and make presentations at their Visitors Center. They also use [Hogan Jazz Archive] as one of the repositories for their oral history initiatives, which are done on video.”

Barnes said park staff members have interviewed a wide variety of musicians for the project in order to preserve their legacies.

One of the older musicians interviewed for the project was Lionel Ferbos, a jazz trumpeter from New Orleans who turns 99 years old in July 2010.

“We interviewed lots of musicians and children of musicians,” Barnes said. “We started with the older, more vulnerable musicians.”

However, as older musicians die, both archives must look to other sources to preserve the legacy of jazz.

“Since most of the early jazz pioneers are now gone, our imperative since 1992 has been preservation and access,” Raeburn said.

|

At left, Lionel Batiste, Sr., another musician interviewed for the Jazz National Historical Park’s oral history project (Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park). |

Barnes also mentioned what separates the park’s oral history project from those of other parks.

“We have video tapes, transcripts, audio,” Barnes said. “A lot of parks have [oral histories] but only audio.”

Barnes spoke about the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park’s current project dealing with the oral histories.

“We want to have a good abstract for each tape,” Barnes said. “We want to make it more accessible and user-friendly to people doing research.”

Research remains a part of the culture. The New Orleans International Music Colloquium hosts a yearly colloquium where it presents scholarly material about New Orleans jazz. The New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park sponsored the colloquium in 2010.

“It’s a lecture series,” Barnes said. “They include scholarly work presented on various topics.”

Barnes even also mentioned some of their material appearing on television.

“We’re partnering with C-SPAN to feature four or five oral histories,” Barnes said.

Raeburn mentioned the difficulty in finding contemporary material as a reason for developing an oral history project.

“When jazz was first emerging, media outlets cast a blind eye upon it,” Raeburn said. “Thus, a ‘paper trail’ of early jazz scarcely exists.”

Their goal remains to preserve the history and culture of New Orleans jazz for future generations.

“We’re doing this so people hear and see the stories of how jazz developed in New Orleans,” Barnes said.

If You Go

Access to the project: Visitors can access the interviews for free at the park’s Visitor Center. Interviews can be requested at the front desk and can last anywhere between one to two hours.

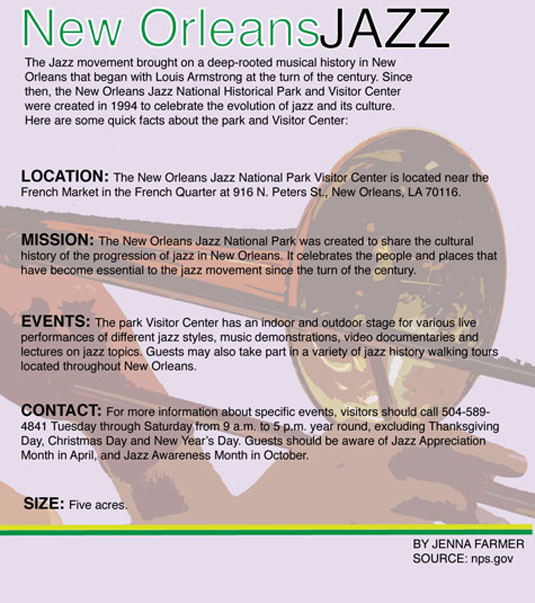

Information graphic designed and prepared by Jenna Farmer.

Comments are Closed