The Voodoo business of the Quarter

NEW ORLEANS — Walking along the streets of New Orleans, it is difficult to ignore a sense of spookiness hanging in the air, especially when dusk sets in and the lively mix of bar-hopping tourists and eccentric locals is rinsed in shadow.

Street performers seem to vanish, replaced by dramatic tour guides parlaying accounts of ghosts, vampires and the beloved buccaneer Jean Lafitte. Blocks upon blocks of festive jazz and family chatter disperse into boisterous patches of masculine laughter and jolly libation and faint trails of alleyway voices.

|

| Figurines in a French Quarter Voodoo shop (Photos by Hunter Stephenson). |

But only when adventuring in the daylight hours does one start to realize the vast number of businesses of a bewildering spectrum dedicated to the Haitian and African-originated religion of Voodoo.

An unusual cornerstone in the French Quarter’s lucrative tourism economy, this taboo cultural thread exemplifies the intriguing way tourism plays into the area’s traditional pastime of blurring legend and fact into romanticized mystique.

“Oh, maybe there’s something to it [Voodoo], but most of it is the usual rubbish, just local folks hoping to make a quick buck or something, give people their kicks,” said Daniel Galli, 43, a tourist from Virginia who left Zombie’s House of Voodoo empty handed.

|

Rev. Zombie’s House of Voodoo. |

Seemingly pulled out of a horror comic a la Creepshow, Zombie’s House of Voodoo, 723 Rue St. Peter, is nestled in an old Georgian-style house with green shutters faded as if worn from a nonexistent beach breeze. The inside is wonderfully unorganized emphasizing a cinematic gaudiness, with piles of carved masks imported from Mexico, cigars, a rear wall littered with baggies filled with roots, wormwood and goat testicles. Hundreds of legitimate-looking “Catholic Voodoo” dolls are for sale, easily the best selection of the shops visited.

|

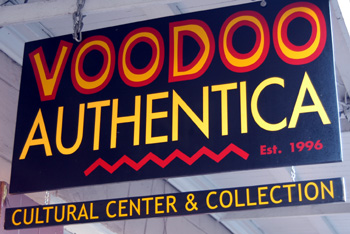

| The Voodoo Authentica shop in the French Quarter. |

Allegedly named after a reverend who died (or did he?) in the 1880s, Galli’s suspicions were confirmed: the college-age staff practiced an eerie slothfulness when spontaneously quizzed on several products’ background information.

Like a top-notch Ed Wood film set, Zombie’s is entertaining nonetheless, especially if on a queasy date or with curious little brother in tow.

Owned by a hip and witty native named Brandi Kelley, Voodoo Authentica, 612 Rue Dumaine, has none of the kooky graveyard-vibe, but perhaps all of the answers.

“There are shops in New Orleans that negate Voodoo’s reputation with tourists, but I think most tourists don’t hold a negative view walking in, that’s a misnomer,” said Kelley. “Some tips to look out for would be altars and employees who speak [the language], those are easy ways for tourists to gage the authenticity of a place since there’s no official certificate.”

Split into three rooms, each decorated in a feminine New Age-African sensibility, Voodoo Authentica is a higher-end boutique specializing in New Orleans-centric Voodoo.

|

| An altar in a Voodoo shop in the French Quarter. |

Unlike many shops in the area including Zombie’s, products are made by local artisans so the profits circulate back into the local community and preserve this spiritual network of which Kelley has been involved since childhood.

Handmade items include a $47 ritual kit containing a handmade beige doll inside a two-foot-long wooden coffin and $75 intricately painted candles.

Limited imported goods range from Haitian drapros (flags) to Mexican art portraying the Day of the Dead to Chinese prosperity frogs.

However, most notable are the 20-plus altars situated throughout the store peppered with dollars and gifts of Bacardi rum and smoked stogies. Several remain outside the sight of employees for a great deal of time, practically daring potential thieves to test the authentica as stereo speakers pulse with the percussive rhythms of Afro-Caribbean meditative jams.

“It doesn’t happen often, but when I notice a few dollars missing, I never wish any harm on them. Although it’s quite bad when it happens, Danh-Gbwe (the Great Serpent) doesn’t like when people take away his rum,” Kelley said not half-jokingly.

|

| The entrance at Esoterica. |

Rounding out the Quarter’s loose categories of voodoo stores is Esoterica Occult Goods, 541 Rue Dumaine St., which melds the foreign aspects of Voodoo with an American Goth rock sensibility that encompasses Satanism, black magic, and, well, lots of black.

An open window allows passer-by to consult with a popular Tarot card reader without stepping indoors (regular customers reportedly prefer a roped-off private backroom complete with a crystal ball).

Against bright red walls stand two shelves displaying hardcover texts by analytical psychologist C.G. Jung and a bottom row of ambiguous, black books embossed with golden pentagrams, one of which is The Book of Shadows.

A friendly cashier on duty is reminiscent of the bald front man for Judas Priest showing European customers the newest selections of brooms and 1980s death metal. Esoterica is worth a laugh, but its relevance to the Crescent City experience will elude most sans fans of the Cure.

Just two blocks down at 724 Rue Dumaine is the Mecca of Haitian Voodoo, the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum, a must-see destination if one wishes to sift through the touristy nick-nacks and get down to the bizarre heart of the local phenomena.

|

Founded in 1972 by a Creole descendent named Charles M. Gandolfo (now deceased), the privately owned museum has switched locations over the years .

The museum now resides in a tidy three-room space loaded with dead animals, imported artifacts and tell-tale yellowed photographs including one of a long deceased, wide-eyed black “mammloi” or midwife holding a human skull.

There are also several photographs of Gandolfo, the founder, who, outfitted in large Hawaiian-style shirts buttoned up over a perma-tan, looks like the Jimmy Buffett of the subculture, but most photos serve as reminders to the legacy of Marie Laveau and her three daughters.

|

| Voodoo shops often feature numerous colorful altars. |

Born in 1794, Laveau, a mulatto woman, brought Voodoo to the upper class whites of New Orleans and soon after, though the extent is still heavily debated, was considered the region’s “Popess of Voodoo.” In today’s Quarter, her name is probably spoken once for every 10 “Jean Lafitte.”

An extremely narrow, creaky-floored hallway leads to two rooms.

The first, “The Occult Room,” is not for the weak stomached and rings with the priviness of viewing a forbidden collection. Upon entrance is the head of an alligator attached to a human-framed body to represent the Spirit of the Louisiana Swamp.

Eyes immediately dart toward all inches of the room in surprise: above the door is an age-old recipe for Haitian zombification, a documented practice, using poisonous powder obtained from a blowfish – which is conveniently mounted nearby. To the right are sizeable glass cases, one contains an assortment of rodent skulls and gris-gris or African charms; the other is filled with irregularly large cross-stitched voodoo dolls with button eyes and caked in dirt of years past.

|

Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo in the French Quarter. |

Engulfed in mystical history after a blistering day of shop-hopping arouses an incessant craving and might call for a little interaction. Instead of using an estranged ex in the middle of rush hour to test the virility of an $8 voodoo doll, why not direct the curiosities in a positive manner (just in case)? On a small piece of paper scribble down a wish, wrap this wish around a dollar bill and drop it into the “Wishing Stump,” a preserved tree trunk carved with moaning faces that supposedly belonged to Marie Laveau II and is now on display in “The Altar Room.”

Adjacent to the stump is the actual altar, where candles flicker in front of a seemingly out-of-place statue of the Virgin Mary. Photographs and aging Polaroids of strangers are splayed across the wall alongside college identification cards and Metrocards.

“Are these people dead?” asks a man with a French accent. Of the six other visitors standing quietly in the room, not one answer; but all seem to be reaching a similar dreary conclusion.

|

The House of Voodoo in the French Quarter offers the wish that “may the curse be with you” on its Rue Dumaine sign. |

Upon leaving, my friend asks the museum’s sole overseer hunched over a small desk if this is, unfortunately, the case.

“No, not at all. People send the museum their photo or a personal belonging when their wish [sic] comes true,” she replied in a calm monotone.

Nine hours later, my wish for a simple cell phone call from a friend goes bust, but it doesn’t trigger. At this time I’m sitting on a bar stool contemplating a way-creepy invite-only Voodoo séance that concluded three hours ago, but continues to grow in my memory. When I finally realize the expiration, sitting on a bed, drunkenly deconstructing a nightmare, I am thankful.

Comments are Closed