House is oldest executive residence

PHILADELPHIA— In the middle of an old historic city where Revolutionary War cannons once careened down cobble stoned streets and were fired at the British, sits a piece of history.

It is hard to imagine that along the same Germantown Avenue here, where soldiers once took up arms alongside each other to fight the British, America’s oldest existing presidential residence still stands.

|

The Deshler-Morris House, where President George Washington lived on different occasions during his presidency (Photo by Bruce Garrison). |

The Germantown White House or Deshler-Morris House, as it is most commonly known, was built by merchant David Deshler in the year of 1750 in hopes of creating an elegant summer home for his family. Spending most of his time in the city, Deshler’s trade in the mercantile business required that he live there for convenience. Still, he longed for a place of rest and relaxation.

“Washington isn’t the only one who made this house famous,” Bernard J. Enright, house volunteer and tour guide, stated.

In 1772, Deshler decided to extend the house, making the once two-room cottage a luxurious nine-room estate.

In 1772, Deshler decided to extend the house, making the once two-room cottage a luxurious nine-room estate.

Although the home remained strictly a summer residence, until the year of 1835, it was its presence as one of the finest in the neighborhood that appealed to President George Washington. This fixation with the estate’s sumptuousness, as well as its distance from the city, made the house a prime location for Washington.

There were also four major cabinet meetings held in the home’s front meeting room.

Here, in November of 1793, Washington met with Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Edmund Randolph, and Henry Knox to discuss issues of politics as well as his recent declaration of neutrality in war between England and France.

Complete with a replica of the plush cherry-red sofa on which Washington reclined his 6-foot-1 frame, and a portrait of defeating-rival British General Howe, who also occupied the house the week following the Battle of Germantown, this room and all the others are left in such a state that if he walked in today, everything would be in its rightful place.

“All of the items within the house have been authenticated by the National Park System as being manufactured between the years of 1750 and the 1800s,” said Enright. “A lot of these pieces are extremely valuable and many of them are actual pieces from [the volunteer’s] personal collections.”

Washington’s first visit in October of 1793, lasting for two weeks, was sparked by the yellow fever epidemic that was taking place several miles away within the city. The house provided refuge for him during this time, but he enjoyed his stay immensely and decided to return the following summer with his family. This time, bringing his wife Martha and the grandchildren, he stayed for a complete two months.

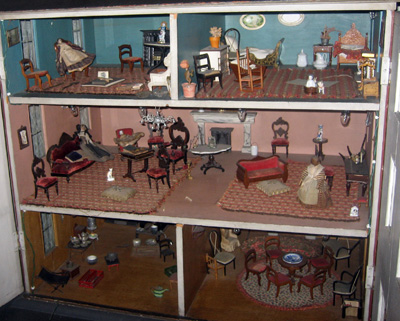

Upstairs, the children’s playroom can still be found as young Nellie and Parke Custis would have played during the summer of 1794. Nellie’s fair-skinned porcelain lap doll sits in her terracotta wicker chair baring a crimson painted smile. While across the room sits a recreation of Noah’s Ark, complete with all represented animals from the biblical story. These simple touches bring life to the home, and are remarkably just as the children would remember them.

| The large doll house in the children’s room is filled with miniatures (Photo by Breyana Penn). |  |

In order to maintain the original aesthetics, the house went through little renovation from the time that Washington and his family stayed there up until its release to the National Park Service in 1948. The final owning family, the Morris’, made the donation. The only major change since that time has been the removal of the additional wing added later that consisted of two bathrooms, but these were not a part of the home’s original design.

Because there has not been any drastic change made to the property since its construction, the house is in desperate need of renovation. The volunteers maintain much of the home’s upkeep, but cannot do the major renewal work that needs to take place.

|

Colonel Isaac Franks was the second owner of the home. Franks owned the home and rented it to Washington during his stay (Photo by Breyana Penn). |

As a result, the Deshler-Morris House will be closed for renovations beginning in January 2007 and is scheduled to remain closed for up to two years. With only half of the funding that was originally intended to pay the costly fees, the $2 million grant will still provide much of what the house desperately needs.

Still, the Deshler-Morris House is not alone in facing their financial woes. Many other historic sites give so much to the community and get fairly little in return due to the lack of donations and funding provided by the government.

In a place where priceless documents unlike any others can be found, and Washington’s personal records of expenses and payments received during his term are held, it is imperative that these items remain available to the public. So much of what we know about his history can be found in this hide-away. Yet, because the house’s main concern comes only from the volunteers, the future of this historic sight is at stake.

“Many people visit the Liberty Bell, or the Constitution Center, but they don’t bother to take the 20-minute cab ride here,” said Enright. “People don’t realize the importance of this historic site. [The volunteers] do all of the guiding; no park rangers do that anymore. We are all that the house has left.”

Although this historical monument will be closing down for a short time, it will reopen a restored venue. Ready to take on the interests of the new found hope that awaits.

|

The formal dining room is set for dinner as it would have been when President George Washington lived in the home (Staff photo). |

If You Go

- Nearby Attractions

- Grumblethorpe

- Residence Inn-City Center

- Valley Green Inn

- Germantown Historical Society

- Germantown Walking Tour

- The facility is open during the months of late April and Early May until late December. The hours of operation are from 1 p.m. until 4 p.m. or by appointment.

- The facility is located at 5442 Germantown Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 19144.

- For more information on the Deshler-Morris House contact an available volunteer at 215-885-3957, or visit http://www.nps.gov/demo

- Fast Fact After the completion of the renovation, the neighboring house will become a Visitor Center for the home, and the facility will now be wheelchair accessible through this addition.

- Fast Fact The Morris family recognized the historic value of the house and did little to change it. Family members lived in the home for more than 100 years before donating it to the National Park Service.

|

The fireplace in the kitchen was not only the place to cook meals, but also a source of heat for that part of the house (Photo by Breyana Penn). |

© University of Miami School of Communication

Comments are Closed