Old fort walls require skill, patience

SAN JUAN, P.R.—Looming 145 feet above sea level, the impregnable walls of San Juan’s forts San Cristóbal and San Felipe del Morro rise sharply above Puerto Rico’s rocky Atlantic shoreline.

At 18 to 25 feet thick, the 3.4 miles of walls that connect the two forts and once encircled the entire colonial Spanish capital have stood for nearly 500 years, outlasting both siege and canon bombardment in five separate battles between 1595 and 1898.

“Impressive isn’t it?” Jose Bastian, a San Juan National Historic Site (SJNHS) stone mason, said in reference to the walls, which stand about six stories high and have withstood more than 300 years of fighting.

|

Masonry worker Ramón “Papo” de Jesús prepares to mix mortar using the park’s mechanical wheel grinder or “lime machine” (Photo by Caitlin Trowbridge).

|

“It’s hard to believe that originally the Spanish intended to build just one portion of the wall at sea level,” he said. “When they understood that one level wasn’t enough to defend the whole area of San Juan, they continued to add on to the wall a little at a time until it was complete.”

Yet, while the walls were built to endure numerous battles and weather constant storms, their preservation and maintenance according to the Spanish’s original 16th century building techniques using limestone, sand and brick dust are among the park’s top priority.

SJNHS Mason Wilfredo Borges notes that the forts’ original walls still stand, but that during U.S. military occupation of the forts in World War II, the U.S. Army used cement as a filler to restore the forts’ deteriorating walls.

“Cement and lime don’t mix,” Bastian said, shaking his head in disapproval at the Army’s actions.

“Cheo,” as Bastian is affectionately called by his co-workers, explained that cement is bad for the forts’ walls because it creates a sealed layer that prevents moisture from entering the walls’ existing limestone mortar, causing them to dry out and crumble further.

“Limestone is a material that needs to breathe,” Bastian said. “It relies on moisture; basically, without water, the limestone turns to powder and dies inside the wall.”

As part of the park’s wall preservation process, Superintendent Walter Chavez points out that the park’s masons are currently working to remove all existing cement from the forts’ walls.

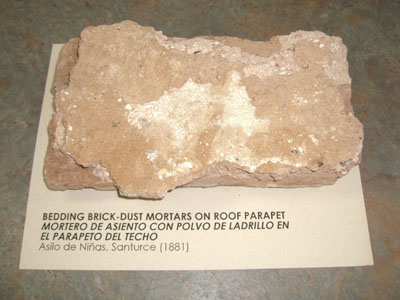

| This original wall sample was used to create a replica of the limestone brick dust mortar used in the top portion of the forts’ walls (Photo by Caitlin Trowbridge). |

|

They, instead, are substituting the Army’s cement “covers” with the walls’ original limestone binder combined with the appropriate aggregate of either sand or brick dust.

“Every time we find cement we remove it, but only if it’s not going to harm the wall,” Bastian said. “If we notice that there is too much cement and it’s too hard to remove without doing damage, we leave it up because eventually the cement will come down by itself.”

“Remember,” Bastian said, winking and pointing his finger for emphasis, “that limestone and cement just don’t go together.”

Having been a stone mason for almost eight years, Bastian is one of the seven tradesmen newly appointed to this permanent position at the park.

“It’s hard to contract for preservation and masonry work,” Chavez said. “Many times the work is not done accurately because there are too few stone masons skilled in creating and administering limestone mortar.”

Chavez remarked that retaining these specialists at the site is also difficult because it takes a minimum of two years of intensive training before a mason can properly apply the Spaniards’ 16th century limestone techniques to the forts’ wall repairs.

“By the time most of these people are done training, it’s time for them to move on to another project elsewhere,” Chavez said with a sigh.

“Fortunately, Edward Colón and his current preservation staff are fantastic at what they do,” Chavez said, smiling approvingly. “People around the island constantly commend us on work well done, as well as on our unique understanding of the limestone techniques we employ.”

|

A SJNHS stone mason applies a fresh layer of mortar while re-facing the recently collapsed portion of the park’s wall (Photo by Caitlin Trowbridge). |

|

In addition to the problems caused by the use of cement, natural elements such a salt water from the ocean and wild vegetation cause further damage to the forts’ walls.

“We have a cloud of salt coming from the sea every morning,” Bastian said, with a slight laugh. “If we are not careful, salt from the water gets trapped inside the wall, crystallizes and then expands, breaking the bricks apart.”

Bastian notes that the walls require some moisture—“just enough to comfortably breathe in and go out”—but too much can be detrimental to the walls’ durability.

“Wall preservation happens everyday,” Bastian said, “because there is something to do here everyday.”

Wild grasses, similar to ivy, cause additional problems. Bastian commented that the same winds that bring salt water from the ocean also carry seeds that get lodged in the walls.

“Since lime is a material good for growth, the roots of these plants grow inside the wall, expand and break the wall apart just like the salt,” he said. “When you are walking around [the park] you will see it.”

Yet, issues of cement, salt and vegetation seemingly pale in comparison to the weight of heavy truck and automobile traffic that caused a portion of the wall to buckle and collapse between forts San Cristóbal and El Morro more than one year ago.

|

Master mason Jose “Cheo” Bastian demonstrates the manner in which the Spanish hand mixed their limestone mortar during the 16th century for one of the park’s wall-based workshops (Photo by Caitlin Trowbridge). |

“The wall collapsed because it couldn’t support San Juan’s heavy traffic,” Borges said. “It was made for horses, not automobiles.”

The park’s masonry team is currently re-facing this portion of the wall with the same 16th century limestone technique in which they preserve it.

“We are a preservation team—so what we do is preserve,” Bastian proudly stated. “Preserve means to restore whatever is damaged in the wall and that is what we do.”

Facility Manager Edwin Colón, a 28-year masonry veteran, explained that this preservation entails collecting a sample of the wall from the area in which the masons are working and making a replica of the wall’s limestone mortar along with its coinciding aggregate of either sand or brick dust.

In the 16th century, the Spanish used five to 10 people to pound limestone and sand into a suitable putty-like mortar with large stick-shaped grinders.

“It takes a long time and a lot of effort,” SJNHS Mason Ramón de Jesús said, referring to the park’s two-year training program in which the masons are responsible for making limestone mortar with this 16th century technique.

Today, the park utilizes a mechanical wheel grinder, which mixes the sand and limestone in under eight minutes.

“We call it the lime machine,” Bastian and de Jesús said, laughing.

“We get as close as we can to the sample because we know that if we maintain the same materials already in the wall it will be like nothing happened or changed,” Bastian said. “The wall will keep going the same way it is and in 500 years will still be here.”

|

The forts’ old powder magazine is used as the laboratory in which replicas of the walls limestone mortar and coordinating aggregates are made (Photo by Caitlin Trowbridge). |

SJNHS Mason Miguel Vázquez believes that it is this 16th century technique that helps maintain the park’s historical importance, drawing tourists to the site from all over the world.

“San Juan is a place where a lot of people come from everywhere,” Vázquez said. “I want to keep this place, my heritage, looking nice for these people.”

If You Go

If you are interested in seeing the masonry work, attending one of San Juan National Historical Site’s wall-based workshops or perhaps even becoming a stone mason, contact Edwin Colón in San Juan at 787-729-6777 or at Edwin_Colon@nps.gov for more information.

Comments are Closed