Restoration preserves centuries-old cannon

SAN JUAN, P.R. — There once was an European navigator and explorer who dreamed big. His voyages during the 15th century across the Atlantic Ocean led him to a sleepy, sun-scorched island in the northeastern Caribbean, then called Boriken by its indigenous inhabitants.

But where the Taíno Indians saw a land for peaceful living, this navigator, Christopher Columbus, saw an ideal stronghold and port for the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean.

To safeguard New World possessions such as Mexico and Peru — which were dependable sources of great wealth in precious gems, gold and silver — and to maintain its trade monopoly, Spain built massive fortifications at key harbors in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

| A cannon being fired during the Spanish-American War (Photo courtesy of the National Historic San Juan Site Archives). |

|

And, historians write, the most critical location was on the island of Puerto Rico, which gained the title of “La Llave de las Americas” (The Key of the Americas).

The Metal Artifacts Conservation Project, run by the National Park Service in partnership with Texas A&M University, is an effort to preserve the cultural and historical heritage of these 400-year-old castles and battlements that encircle Old San Juan — protected today as part of San Juan National Historic Site.

A $175,000 project, it involves the use of special techniques in conserving bronze and iron cannons, the archetypal form of artillery employed by the Spanish in warfare.

Conservation work of the artifacts — 24 obsolete cannons and 352 shells in total — is taking place at the grounds of Castillo de San Felipe del Morro, the chief tourist attraction in Old San Juan.

With a dramatic stretch of the Atlantic Ocean as a backdrop, the six-level El Morro – a term for “headland” or “promontory” in Spanish — stands magnificently at the entrance to the San Juan Harbor, built in by the Spaniards to prevent attack by water.

Javier Martinez, museum technician for the San Juan National Historic Site, and Peter Fix, an archaeologist at Texas A&M who trained the local staff in special techniques, are in charge of the conservation project.

|

Javier Martinez, museum technician, working on a cast iron cannon (Photo courtesy of Javier Martínez of the National Historic San Juan Site Archives.) |

“This is the first time a project of this magnitude is being carried out in San Juan,” said Martinez. “It is a true endeavor in preserving our historic integrity.”

The bronze cannons show very little sign of material degradation and only their surfaces will receive treatment to prevent corrosion.

However, the treatment methodology for the 20 cast iron cannons, which face critical material degradation due to exposure to the harsh coastal environment, involves cautious procedures.

Following documentation of the cannons to preserve diagnostic features and their removal from the cement pedestals, the paint layers of the artifacts are stripped and the surface lightly cleaned mechanically with an air-scribe.

The surface of the cannons must then be stabilized — the chloride ions present in the surface, which accelerate the deterioration of the object must be removed and the ferrous corrosion of the surface layers reduced as best as possible — a process that takes several months to complete.

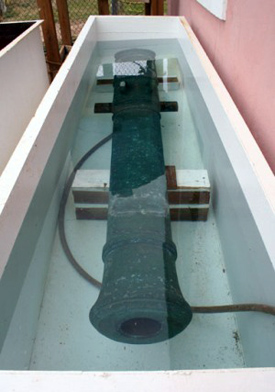

Three cannons are treated at a time, the current ones having been soaked in containers in a solution of three to five percent by weight of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) with reverse osmosis water since April.

|

A bronze cannon in a vat at San Juan National Historical Site (Photo by Javier Martínez, courtesy of the National Historic San Juan Site Archives). |

The level of chloride removal is monitored using quantitative mercuric nitrate titration and after several months or if the level of chlorides plateau the solution, it has to be replaced with a fresh solution of the same percentages.

When this process is complete, the remaining corrosion layers can be assessed to determine if they are likely to facture from the metal core.

The surface of the cannon will then dewatered with ethanol and no less than three coats of reagent grade tannic acid in a 10 percent (by weight) solution with ethanol, which has to be applied over a 24-hour period.

Tannic acid in contact with ferrous ions forms ferrous tannins that inhibit corrosion and protect the cannon from air, moisture and contaminants.

Ideally, after treatment the artifacts should be stored and displayed at the lowest possible relative humidity.

However, this notion is very difficult to achieve at San Juan, where cannons give a sense of place to the forts and are to continue to be enjoyed by the visiting public. Therefore, a final sealant is applied to fill the bore with molten microcrystalline wax after the tannic acid treatment.

The group of 352 shells has been treated since August 2006 in two different solutions to stabilize metal. One solution consists of sodium carbonate (NaCO3) and the other is sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

| Artillery shells that are being treated in sodium carbonate (Photo by Javier Martínez, courtesy of the National Historic San Juan Site Archives). |

|

Samples have been sent every two weeks for analysis at Texas A&M and should be ready in another month or two, the restorers said.

The artillery will be displayed in both El Morro and San Cristobal forts — the latter, which was built to prevent attack by land.

In its main plaza and the casemate next to the bookstore, visitors can enjoy a video on the techniques employed to fire cannons. How far the ball would reach depended on its inclination and the amount of powder used — up to a six-mile range.

During wartime, cannons could be neutralized by putting using a bigger shell than needed, causing an explosion that would seal the cannon or by hitting it with a hammer to cause bumps — the reason some of the San Juan cannons are missing half of their body.

“A lot of visitors wonder why the forts are home to such a small number of cannons,” Martinez said.

The rangers at El Morro and San Cristobal are quick to remind the tourists that the island enjoyed centuries of peace — before being conquered by the U.S in 1898, Puerto Rico only experienced one major attack by the English in 1797 — a memorable victory over successful Lt.-Gen. Abercromby, who failed to overcome Puerto Rico’s first line of defense. After the Spanish-American War, some of the cannons were melt or sent back to Spain.

|

A cannon while being lifted by a large crane used to put the bronze cannon in the vat (Photo by Javier Martínez, courtesy of the National Historic San Juan Site Archives). |

Comments are Closed