Museum celebrates Miwok, Paiute cultures

YOSEMITE VALLEY, Calif.— Inside the Yosemite Museum, Phil Johnson quietly sits in front of a re-created Indian home chipping away at what only appears to be a shiny, black stone.

It is not any type of stone; it is an obsidian stone and, in one hour, Johnson has turned the stone into a perfect blade arrow point through an ancient process known as flint knapping.

“The two Indian tribes would meet every year for trade and commerce purposes, and that is how the obsidian stone got into the hands of the Miwok Indians in the Valley,” Johnson said.

The Yosemite Museum houses the Indian Cultural Exhibit, which displays the history of the Paiute and Miwok people from 1850 until today. Johnson, who is of Miwok and Paiute heritage, is one of the three demonstrators at the exhibit along with Julia Parker and Ben Cunningham-Summerfield.

The first Indians came across the Yosemite region some 4,000 years ago, but the Miwok and Paiute people traveled to Yosemite and created the most well known settlements centuries later due to the expanding Sacramento and San Joaquin people.

The Yosemite Indians derive from ancient times, but little remains in Yosemite from those times. What is known from the ancient Yosemite Indians is that the utilitarian objects they constructed such as bowls and spoons were delicately and elegantly made. This type of work in turn influenced the Miwok and Paiute people who meticulously crafted everything from baskets to clothing.

The Miwoks settled in the Yosemite Valley and they called it “Ahwahnee,” which signifies “place of a gaping mouth,” while the Paiute people resided in the east side of the Sierra Crest along Mono Lake.

| This type of headdress was worn by Miwok dancers, such as Francisco Georgely, during ceremonial dances in the late 19th century. Georgely was an important person at Yosemite because he acted as a go-between for his people and communicating with the non-Indians (Photo by Elena Chiriboga). |  |

The museum is rich in information concerning the two tribes. Artifacts such as handmade baby cradles, jewelry and woven baskets are preserved inside glass casings for visitors to get a glimpse at the intricate crafts for which the tribes prided themselves.

“The daily activities of men and women were separate and, as demonstrators, Ben, Julia and I are supposed to perform daily work for the public on a project of our choice that represents traditional work of the Indians,” commented Johnson while spreading out the various blade arrows he has created.

The group is led by Julia Parker who is the senior interpreter and a renowned intertribal style basket weaver. She took over the position from Lucy Telles, who was the main cultural demonstrator and also Parker’s basket weaving instructor. Parker has been of the most significant people associated with the park because of her determination to preserve the traditional Indian heritage from games to tools to basketry.

Parker is certainly appreciated by not only the outside community, but also her co-workers look to her to gain insight on their culture.

|

A re-created umacha sits in front of the entrance to the Yosemite Museum. This was considered a typical Miwok and Paiute early home and was made from cedar bark (Photo by Elena Chiriboga). |

“Working with Julia is wonderful. She just has so much knowledge concerning the traditions,” commented Johnson.

Daily demonstrations by Parker include basket weaving and plant preparations, which were the two most traditional activities for Miwok and Paiute women. Performing these traditional activities forms the bond between Parker and her ancesry to reveal to visitors the cultural importance that acient heritage has on Yosemite.

“I visited the park quite a while ago and Julia was performing a basket weaving demonstration. I was so impressed by her skill and how eager she was to show the visitors in the park what the Indian women would do,” said park visitor Nancy Gutierrez.

Basketry played an important role in the lives of the Yosemite Indian women; they were used for many domestic chores, and the plants used to make the baskets such as willow, redbud and sumac were all native to the Yosemite region.

Lucy Telles was considered the most celebrated basket weaver of Paiute descent and some of her baskets are featured at the Yosemite Museum. The baskets at the museum are large in size and decorated with shades of reds, blues and browns.

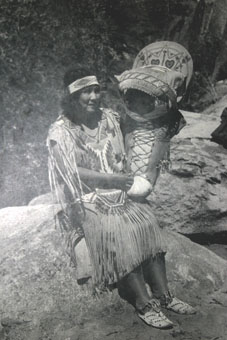

| At right, a typical baby cradle during the 19th century for the Miwoks and Paiutes (Photo by Elena Chiriboga). Below, a life-size sculpture of Chief Lemee at the entrance of the museum (Photo by Elena Chiriboga). Next, a black and white photograph of Lucy Telles with her child in a traditional baby cradle (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). Last, a 19th century photograph of Chief Lemee with ceremonial regalia adorned with clam shell necklaces (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |  |

Women created baskets mostly for everyday purposes, but they also entered them in competitions with other basket weavers for prize money. Telles also made a living by selling her baskets to visitors who wanted an authentic piece of Paiute cultural life.

“Most of the visitors have questions concerning what the baskets were made of and how they were constructed,” states Johnson.

This is apparent when a visiting family stares at awe into the case containing Telles’s basket and the mother of the family, Maureen Connelly, commented, “This design is incredible! This took the woman four years to make.”

Ben Cunningham-Summerfield usually demonstrates traditional Miwok song and dance for local school children groups in the re-created 19th century Indian Village of Ahwahnee found behind the Indian Museum. In the village, which was originally built during the 1920s, visitors can enjoy a self-guided tour through Miwok bark houses, a ceremonial roundhouse and a sweathouse.

Ben Cunningham-Summerfield usually demonstrates traditional Miwok song and dance for local school children groups in the re-created 19th century Indian Village of Ahwahnee found behind the Indian Museum. In the village, which was originally built during the 1920s, visitors can enjoy a self-guided tour through Miwok bark houses, a ceremonial roundhouse and a sweathouse.

The Yosemite Indians lived in what was most commonly known as an “umacha,” and these structures were made from local cedar bark that had been dead for about two years.

The reconstructed village contains three umachas that are relatively large in size, and visitors can walk into the dwellings to get a first hand experience of early Indian living. Looking up inside the umachas reveals an opening that allowed for the release of smoke when a fire was lit.

“The Indian village keeps being reconstructed because it is a hands-on exhibit. Groups of school children love running around throughout the village,” stated Johnson.

Found in large villages was the ceremonial roundhouse, where religious events occurred. The original roundhouse in the re-created village, built in 1973, has since been replaced by one created in 1992. The current structure displays the type of roundhouse that the Miwoks built once they made connections with non-Indian people. They began to incorporate a cedar bark roof once these contacts were made because of the facility of preserving them.

The appearance of European settlers in the 1850s prompted the Miwok living in the valley to produce building styles that were common among Euro-Americans. They built the Miwok cabins, which were adopted until 1920s, and incorporated a mixture of traditional Miwok elements and those of the Euro-Americans. The cabins were constructed on the floor and built with a roof that contained a hole so that fire could escape, similar to the umachas.

The sweathouse was also a unique and interesting part of Miwok and Paiute life as it served to aid men in their hunting expeditions. The hunter would spend hours in the sweathouse and prepare himself for deer hunting by smoothing wormwood or distinctive smelling plants on his body so that the animals would not be able to pick up a human scent.

The sweathouse was also a unique and interesting part of Miwok and Paiute life as it served to aid men in their hunting expeditions. The hunter would spend hours in the sweathouse and prepare himself for deer hunting by smoothing wormwood or distinctive smelling plants on his body so that the animals would not be able to pick up a human scent.

Not limited to use by the three demonstrators, the local Native American community continue to hold functions in the village at the ceremonial roundhouse for special occasions. Most of the locals come from Mariposa County because it encompasses Yosemite National Park.

“Once a year, a large gathering occurs in the Ahwahnee Village and hosts a dance in traditional Indian regalia. It is very popular gathering in the local area,” commented Johnson.

Walking around the small museum one can notice that the Miwoks and Paiutes certainly distinguished their everyday clothing from their ceremonial outfits.

“Most jewelry with beads was made for everyday use. A lot of what is preserved here was casual wear. The clam shell necklaces are what were for special use,” said Johnson.

A brightly beaded buckskin dress at the museum signifies an outfit worn for a special occasion. The Miwoks and Paiute decorated the buckskin dresses with colorful beads, intricately woven into patterns on the dress. These beads were not constructed by the Yosemite Indians and were in fact brought from Europe.

Different types of skins were used by the Yosemite Indians throughout different parts of the year. In the re-created home of a typical Miwok family, found inside the museum, three types of skins hang on the wall. Fox skin was used during the cold weather, deerskin was appropriate for everyday use and after the California Gold rush cloth became a popular material for the Indians.

Johnson stared down at his arrow points, reflecting on ancient years of tradition, and then spoke.

“I’ve never been much of a traveler since living here. I don’t know why,” he said

“I’ve never been much of a traveler since living here. I don’t know why,” he said

Perhaps the man who has Miwok and Paiute heritage feels he cannot stray far from the place where all his ancestry is from and believes it is his duty to preserve the culture and teach those who come visit the beautiful park.

If You Go…

- The Yosemite Museum is located in Yosemite Village, next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center in Yosemite National Park, Calif. 95389.

- The reconstructed Indian Village of Ahwahnee is located behind the museum and is open at all hours.

- Hours of operation are 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily for the museum.

- Admission is free.

- Call 209-372-0200 for more information or visit: http://www.nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/historic.htm

Comments are Closed