Pythons causing problems in Everglades

HOMESTEAD, Fla. — The Everglades National Park is a welcoming refuge for wildlife and tourists alike. The same goes for the invasive, non-native snake population that has infiltrated the park ecosystem as its new home.

“We have a python problem in the park,” said Everglades National Park Ranger Erica Baker. “They don’t bite, but they are dangerous. They are constrictor snakes.”

An estimated population of 100,000 Burmese pythons and other foreign snake species are slithering around the Everglades and into the surrounding areas.

| Click on the video at right to view an audio slide show about the Burmese pythons problem in Everglades National Park prepared and narrated by writer Nina Markowitz. |

“The snake problem is thought to be from Hurricane Andrew — the snakes that were impregnated were blown over into the park and then laid their eggs,” Baker said.

Whether released by overwhelmed pet owners or destroyed pet stores during Hurricane Andrew in 1993, pythons are thriving in the Everglades.

“They lay up to 90 eggs at a time. The females can retain sperm and lay an additional 90 eggs,” Baker said. “So one snake that was impregnated has the potential of laying up to 180 eggs.”

| At right, the dense plantation of the Everglades National Park provides the perfect habitat for pythons (Photos by Nina Markowitz). Next, the Everglades provides ample hiding spots for pythons. |  |

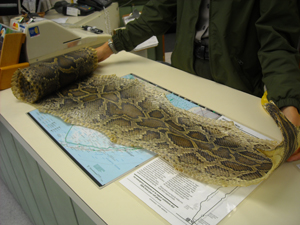

The pythons grow 10 or event 20 feet in length. Baker had in her Alligator Alley office a python hide of a snake estimated at 11 feet in length. Sheer size makes the snakes dangerous predators, quickly multiplying and thriving in the swampy Everglades ecosystem.

As foreign species, they have no natural predators. Yet as a predator themselves, they have become very successful in munching on some of the Everglades’ most endangered animals.

“They’re killing off our small mammal population, so we aren’t seeing any small mammals in the Everglades anymore,” Baker said.

“They’re killing off our small mammal population, so we aren’t seeing any small mammals in the Everglades anymore,” Baker said.

And, as the stomach contents of all captured pythons is always analyzed, park rangers now realize that the snakes’ appetites sometimes rival the native alligators.

“They will try to eat each other,” Baker said. “There’s been evidence of both.”

The Everglades National Park staff works to preserve the wildlife within its boundaries from harm. A specific group of 10 people has been established to counteract the invasive snake population. This special hunting team is made up of volunteers and law enforcement rangers — the only rangers permitted to shoot a python within the park.

“They’ll go out once a month and they’ll look for pythons. Then it would be given over to the researchers to examine the stomach contents,” Baker said.

Since the Everglades is a national park, hunting is generally not allowed. But in surrounding areas, including Big Cyprus National Preserve, licensed hunting is permitted.

It is for this reason the non-profit organization Nature Conservancy launched the Python Patrol in spring 2009, training officials and citizens alike how to capture non-native snake species outside of the boundaries of the Everglades National Park with a specific focus on the Florida Keys. Alison Higgins is responsible for the Python Patrol in the Florida Keys.

“We are trained to respond to already sighted pythons for the Keys, where we don’t have a breeding population yet,” Higgins said. “Only random snakes that are dumped or escaped, or snakes coming from the Everglades.”

Participants are trained on the “Eyes and Ears Team” or the “Responding Team.” The first is made up of citizens who drive through the Everglades looking for snakes sunbathing in plain view. These people tend to have jobs, which have them out on the road often, such as a police officer or postal worker. When they spot a snake, they call for a responder to come to the scene who is trained to capture the python.

|

At left, Park Ranger Erica Baker unrolls the hide of an 11-foot python discovered in the Everglades at Shark Valley. Below, a sign at the Everglades National Park depicts the delicate nature of the ecosystem that now has been thrown off since the introduction of the python. Last, a close-up look at a python hide. |

“Our goal is to be able to get out there within 20 minutes,” said. “Before the critter crawls off.”

Responders are specifically taught how to wear the snake out before they go in for the grab. They are also called to the scene when snakes are spotted, instead of seeking snakes out.

“Snakes are super, super cryptic,” Higgins said. “About two to three dozen snakes have been caught.”

Higgins said the Nature Conservatory has a three-stage philosophy when it comes to invasive exotic animals released into the wild.

The first step focuses on prevention— teaching people how to be responsible pet owners or creating opportunities for pet owners hand over their exotic animals instead of releasing them into the wild.

The first step focuses on prevention— teaching people how to be responsible pet owners or creating opportunities for pet owners hand over their exotic animals instead of releasing them into the wild.

The second step is early detection and rapid response. This stage is what the Python Patrol is all about— capturing invasive snakes before they have the chance to become breeding populations.

And third step is control. At this point, all that can be done is controlling the invasive species as best as possible so it does not throw the natural ecosystem off-kilter. This stage requires a lot of effort, and a lot of money.

Now, the Nature Conservancy is pushing for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s “Lacey Act” to pass. This is federal legislation that will prohibit Burmese pythons and eight other large constrictor snakes from being imported into the United States.

Ranger Baker supports the Lacey Act.

“I think that it’s a very important and effective measure and I really think something like that will help us from seeing problems like this in the future for other species,” she said.

Yet when it comes to eradicating the foreign snake species and returning to the Everglades ecosystem of old, Baker is much less hopeful.

The snakes are thriving in the swamps of South Florida and not even the cold winter of 2010 was enough to knock their numbers down in a significant manner.

The snakes are thriving in the swamps of South Florida and not even the cold winter of 2010 was enough to knock their numbers down in a significant manner.

“[The cold] didn’t kill as many as the media perpetuates,” Baker said. “It killed some, but not enough to make a difference.”

Baker feels there is little anyone can do to rid the snakes now that they are at home in the Everglades.

“At some point we’ll just have to accept that they’re part of our ecosystem. There are so many we may never be able to get rid of them,” she said.

What You Should Know…

If you spot a snake in South Florida, contact the Python Patrol at 1-888-IVEGOT1 or at www.IVEGOT1.com

Comments are Closed