Unwanted pythons move into Everglades

HOMESTEAD, Fla.— The story first exploded on the pages of the National Examiner, typically not the most common source for news, but this story is real – Pythons are invading the Florida Everglades.

In January 2003, hundreds of Everglades National Park tourists witnessed a 24-hour struggle between an alligator and a python at Royal Palm, one of the most popular visitor sites in the park.

Skip Snow, a wildlife biologist at Everglades National Park, said it best.

“It was a big deal. I pretty much assigned myself to see how big of a problem this really is.”

|

| An alligator and a large python battle for their lives at Royal Palm in Everglades National Park (Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer). |

Snow and other biologists at the park decided the python situation needed more attention because the exotic snake poses a threat on many levels.

“Our issue with pythons is a result of the pet trade,” Snow said. “You can buy them for as little as $20 at a flea market. Maybe as much at $40 to $70 in a pet store. The fact that you can buy them at a fairly disposable price and that there are so many out there that if you had the desire to get rid of it you would have little invested.”

According to Snow, people who have bought them possibly are unknowing that Burmese pythons can grow up to 6.096 meters (20 feet) in length. Often times they become a burden, both financially and in terms of care for pet owners.

Between 1995 and 2005, 212 Burmese pythons were captured and removed from the park. The largest being 4.8768 meters (16 feet) long and weighing in at 70.76 kilograms (156 pounds).

Many people falsely believe that releasing them into the wild is the most humane effort they can make. Although Burmese pythons have acclimated almost flawlessly to the everglades, it is not good for the delicate ecosystem. Ten years ago, biologists were still unsure if the pythons were breeding, but recent research has confirmed the problem. Snow has found females with as many as 50 eggs developing inside.

Threats posed by pythons

There are four main concerns about the Burmese python. First off, they are eating native animals.

“They’re known to hang around bird rookeries and wading birds are one of the main resources we are trying to protect and restore,” Snow explained.

|

A python and alligator tangle at Royal Palm in Everglades National Park (Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer). |

These pythons live for 20 to 25 years and can eat a lot in their lifetime.

“Right now we’ve found everything from small native mice and native cotton rats, possums, grey squirrels, muskrats, bobcats, and birds. There is the one case when an alligator was eaten, or attempted to be eaten, where both animals died,” Snow said.

The alligator incident made headlines last October around the world. However, Snow said this appears to be an isolated incident, but is still weary of the situation.

“I do think there is no reason to think that pythons wouldn’t be capable of and maybe even interested in eating smaller alligators, hatchlings, etcetera. We haven’t seen that yet in the stomach, but I think it’s only a matter of time,” Snow said.

The second concern with the python presence is that they are competing with native predators such as the bobcat. Bobcats are an endangered species, so Snow was even more concerned upon finding a bobcat claw inside one of the removed pythons from the Everglades. Pythons are threatening this particular species on two-fronts: competition for food and as food themselves.

The third concern is the competition for dry holes, hollow logs, tip-ups (where a tree falls over and makes a cave), and other places that over 25 native snakes in the Everglades also enjoy for housing.

“So if real estate is in short supply we’re wondering what kind of competition there might be for these micro-habitats,” Snow said.

Although cross-breeding between the exotic snake and the native snakes is not possible, the fourth concern is exotic diseases that the Burmese pythons may carry and could be transferable to native snakes. This has not been proven or unproven at this point. However, Snow explained that there are cases when these exotic diseases have been decimating for museum collections or zoo collections of pythons or boas.

|

Skip Snow, a wildlife biologist at Everglades National Park, examines a python in his lab (Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer). |

The last concern is human safety. What threat do these animals have on humans that may be visiting, exploring, researching or studying in the Everglades National Park in South Florida? All of these concerns are in an on-going study.

Python Pete

Since the python problem in the everglades is a completely unique situation, many pilot programs are being initiated to address the issue. One of the more interesting initiatives is Python Pete – a year and half old beagle being trained to track Burmese pythons.

Lori Oberhofer is another Everglades wildlife technician that works closely with Skip Snow on the python issue. Oberhofer previously worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Guam, where a unique program inspired a new project in the Everglades.

The brown Treesnake, an exotic species in Guam, has been decimating native wildlife. Wildlife experts fear that the snake is going to move to Hawaii through cargo and various other passages and wreck havoc to the Hawaiian ecosystem.

“One of the tools they use is either a beagle or a Jack Russell Terrier,” Oberhofer explained. “I thought it would be a really interesting, fun project to see if I could train a dog to detect pythons.”

Oberhofer invested in Pete with her own funds and got him as a puppy. She brings him to works everyday and uses live snakes to train him.

“Basically we would let him smell the snakes and every time he smells them he’d get a reward. And that progressed to hiding the snakes behind the sofa, under the chair and soon moved to outside to hide the snake at longer distances.”

Oberhofer creates a scent rail by dragging a live python in a laundry bag outside in the grass by the research facilities, leaving the snake at the end of the trail. Pete then gets his special red harness and lease put on that signify “work time.”

Training Pete is not Oberhofer’s only responsibilities at Everglades National Park, and that has hindered the speed of the training process.

“At this point the process has been a lot slower than I originally wanted it to,” Oberhofer said. “I’m just at this stage where I’m trying to take him out on sightings.”

There is a small set-back using Pete as a tracking tool.

“He wimps out; it is a problem,” Snow said.

| A crowd gathers to witness a battle between an alligator and a python at Royal Palm in the southern part of the Everglades park (Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer). |

|

Because of the climate in South Florida, Pete has a working period of about 10 to 15 minutes before he “overheats.”

“He needs a better work ethic,” Oberhofer joked. “But apparently that’s about the same as the dog teams in Guam; it’s so hot and humid so it’s about the same. They have to take a break then try again.”

The ultimate goal is to get Pete to be a first responder to reported sightings. Oberhofer hopes that Pete will eventually be good enough so she can walk roadside with him and he can spot pythons.

Although Pete has shown great potential in the first year and half of training, the success of the program is still unknown.

“In Guam, they use them sniffing around cargo and airports, it’s a lot more contained. Taking a dog out in uncharted terrain, it’s a lot tougher for a dog,” Oberhofer explained.

While on the hunt, Pete remains on a short lease and will never be free roaming, both Oberhofer and Snow assured. This way he will not be in harm’s way of snakes, alligators, or other predators of the everglades.

But Pete isn’t even afraid of the snakes. “Pete is blissfully ignorant, and excited to do his job. Hence, the short leash,” Snow said.

Until his training is completed, Pete is serving another very important role to the python program at Everglades National Park.

“Meanwhile, he’s a PR dog – a media dog,” Oberhofer said lightheartedly. “He does a great job. He’s an experiment; one potential control method that we’re working on.”

Other possible solutions

In addition to Pete, there are several other initiatives taking place to attempt to control and eventually eradicate the python problem.

A simple idea to deal with the situation is traps. There are various kinds that might work for this situation, certain traps funnel snakes into them and others have bait inside of them to attract the snake – either by a rodent or pheromones. All of these traps need more testing to see if they are effective.

|

Pythons, such as this 15-foot example, are frequently found in the Everglades National Park (Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer). |

More testing requires more funding, which is one of the main challenges in all of these possible solutions is funding and resources. The ideas are there, but without the proper funding, it is difficult for biologists to give each idea a fair chance.

Another program was initiated last December using radio tagged pythons to lead the biologists to other untagged pythons. By use of the radio tracking device the biologists are able to go locate the untagged snakes and remove them, while leaving the other radio tagged snakes to locate more pythons.

“It’s this concept known in wildlife management as the Judas animal, because of the betrayal concept,” Snow explained. “It’s been used for years for goat control, pig control because those animals are gregarious; they often attract other. I’m not aware that it’s ever been done with snakes for control.”

In the first phase of the radio tracking program, a scary hypothesis was confirmed, the pythons are certainly not restricted to road or canal corridors where all 212 have been removed, but they also inhabit native tree islands away from the roads.

Prevention

Step one in prevention is education and awareness. Using some of the funds from the Environmental Education Program allocated by the government, Snow and Oberhofer are leading a small campaign called “Don’t let it loose, be a responsible pet owner.”

The campaign, still very small due to funding, is starting out with just stickers.

“We want to ultimately have some posters and bookmarks that would give the reasons why you don’t want to release,” Snow said. “And maybe have materials for the pet stores to display and would be able to give out when an animal was bought to be taken home.”

“There’s never been a case made that we’re aware of, including the law enforcement, because they would literally have to see the person release it,” Snow explained. “And that just doesn’t happen.”

Since the belief is that many released pets are a result of a situation that started with a young child wanting the pet – kids are the focus of the campaign. “We’re trying to pursue this especially in the classrooms, especially with the kids,” Snow said.

State of Florida Action

Releasing an exotic animal is a first-degree misdemeanor in the state of Florida, punishable by up to one year in prison and $1,000 in fines. However, because of the way the law is written it has not been effective.

More effective laws are making their way to be put on the books. Florida State Representative Ralph Poppel of Brevard County has written Florida House Bill 1459, which recently just passed in a House Committee. The bill requires a $100 license for exotic reptiles including Burmese pythons.

“This $20 animal now cost $120,” Snow explained. “So maybe when mom and dad are in the pet store and their 12-year-old wants it, $20 isn’t much. But if they have to pay a $100 registration fee, they might stop and think about it.”

Since the bill is just out of committee, it is unclear if the license fee will be annual or if current pet owners would be required to pay the fee. The fee is slated to go to the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission of Florida.

|

Python Pete, a beagle trained to find pythons in the wild, and biologist Lori Oberhofer on a training session in the Everglades (Photo by Skip Snow). |

The bill, which has an effective date of July 1, 2006, is also attempting to require notification to the state when the animal is given away, sold, or traded. This is an effort to help track the animal, and further prevent releases.

The state is also sponsoring a pilot amnesty day supported by Petco, a national pet store chain founded in 1965, with a commitment to education and pet care. The day is being set for May in Orlando.

“They still have some details to work out. If the legislation goes through they’re concerned about mass dumping,” Snow said.

The event will likely be advertised to bring all unwanted exotic reptiles to a certain location yet to be determined. Veterinarians will be on hand to examine the animals and provide humane euthanasia if necessary.

Many pet owners feel that letting their exotic animal loose in the park is the best thing for the animal, but they may be wrong. Pythons have been found run over by cars, burned over by fires, eaten by alligators, and struck by tractors in the surrounding farm fields.

“[Releasing your pet is] not good for the animal, it’s not good for the environment, and it’s against the law,” Snow summarized.

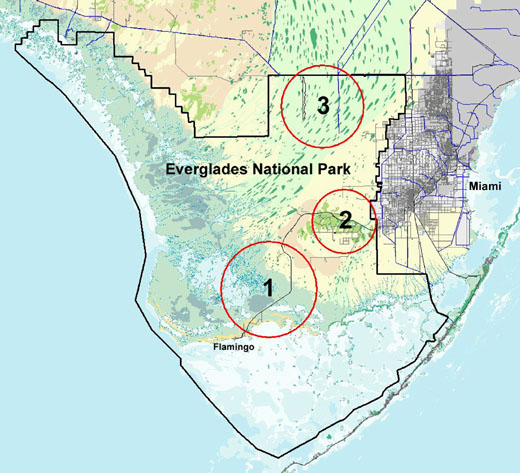

Pythons have been found in three main areas of the Everglades National Park (Map courtesy

of National Park Service).

Comments are Closed