Fort’s history tells stories of hardship

DRY TORTUGAS, Fla.— In the middle of the Gulf of Mexico, the grandest military coastal fortress of the 19th century still remains as it once did 157 years ago. A combination of brick and steel was erected on the island of Garden Key, one of seven islands, making up what the Spanish explorer, Juan Ponce de Leon called the Dry Tortugas.

Ponce de Leon discovered the islands almost 70 miles west of Key West in 1513. They are called dry because there is no fresh water on the island and tortugas because it was a location where turtles nested and they became the most abundant food source on the island for sailors.

The name would become a warning for sailors to avoid this area and it would reflect the rough life those future inhabitants of the islands would experience on these islands.

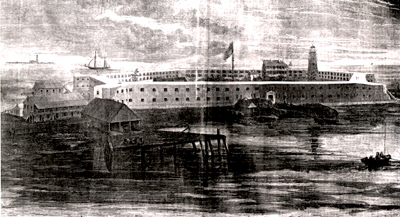

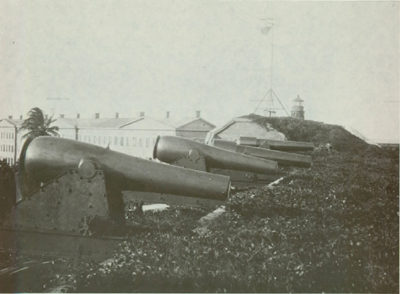

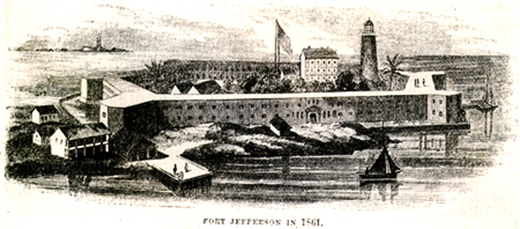

|

Fort Jefferson as portrayed in Harper’s magazine in 1861 (Image courtesy of Richter Library, University of Miami). |

The history of Fort Jefferson is one of struggle, death and suffering. The fort was created out of military service in hopes of ensuring the safety of the United States’ Southern region. It is a history that Dry Tortugas National Park Ranger Mike Ryan is willing to share. Ryan, the lead interpretive ranger, leans against the corner of his desk in his office, a converted ‘case mate,’ once an arch-shaped room used to store a 10-inch cannon called a Rodman.

Ryan described why he is passionate about the history of Fort Jefferson.

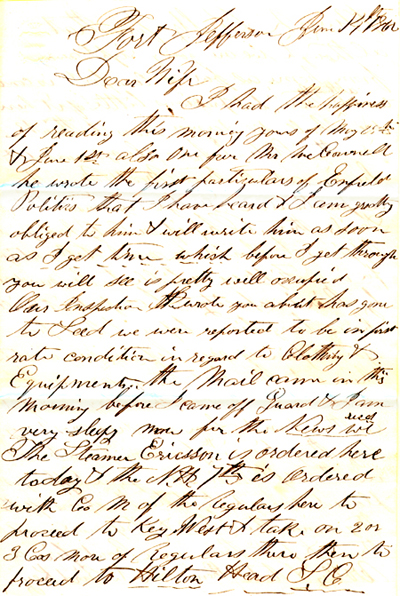

|

A letter from Calvin Shedd to his wife that shows a Fort Jefferson postmark (Image courtesy of Richter Library, University of Miami). |

“It’s a very complex story and it is not well documented. There are not lots of secondary sources.

“As a child I grew up near these forts, and it got a hook into me. I spent a lot of time in archival areas. This is the type of resource that excites me.”

In 1829, the United States government realized the location of the islands would be an ideal location to guard the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, and also control trade routes to Louisiana. The government had to create a presence to guard this area and they did so by planning to construct a military facility on one of the islands in the Dry Tortugas.

After the U.S. government purchased Florida from Spain in 1822, Commodore David Porter was sent by the Navy to the islands in December of 1824 to determine if the islands were suitable to build a military fortress. Porter was not optimistic when he saw the islands and records of his letters preserved by the National Park Service reflect his disgust in the choice for a military facility in the Dry Tortugas:

“…[B]ut they have no fresh water and furnish scarcely land enough to place a fortification and it is doubtful if they have solidity enough to bear one,” according to one of the letters written by David Porter.

|

One of Calvin Shedd’s letters to his family written from Fort Jefferson (Image courtesy of Richter Library, University of Miami). |

Porter’s views were not shared by everyone in the navy when his warning was not heeded in 1829.

Commodore John Rogers and a group of engineers went to the Dry Tortugas and thought it would be a great location for a military fort:

“A naval force designed to control the navigation of the Gulf could not desire a better position than Key West or the Tortugas,” according to a letter written by John Rogers that is preserved by the National Park Service.

Rogers believed the islands would be able to sustain a fortified structure, but there was one problem he saw on the islands: There was no fresh water. This did not deter him and Rogers believed creating cisterns on the islands to gather rain water would be sufficient.

“Fort Jefferson was designed to collect rain water for a garrison of two thousand. The top is designed to collect water. Under each of the rooms are large cisterns. Many were destroyed when the fort sank, but several are used,” Ryan explained as he illustrated with his arms how water travels down the case mate in his office and goes down to an underground cistern.

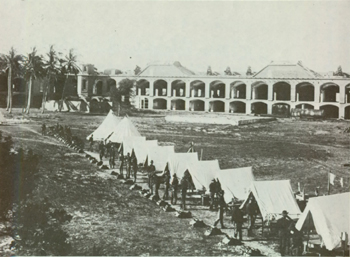

|

Looking from the officer’s quarters across the parade ground in May 1898 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

The cisterns Ryan talks about are a complex system of channels collecting rainwater under the fort, but in the early 1850s the fort gradually started to sink.

Most of the cisterns were destroyed by the sinking of the fort, but some still remained functional. To this day, the rangers living on Garden Key use the cisterns to collect and use water just as the soldiers who once lived there did.

In 1844, the 28th Congress approved $50,000 towards the construction of the fort which was called the Fortification Bill. This was the initial step, which guaranteed financial support in building the fort.

In 1845, Maj. Hartnan Bache was assigned to oversee the preparation and construction of the fort. Chief Engineer Joseph Totten was later assigned to supervise construction. Even though the fortress was created to serve as a refueling and supply facility for the Navy, it was also designed to carry 400 cannons, included on all its sides and one hot shot furnace, which fires flaming cannon balls.

Ryan explained the importance of how Totten protected the fort’s soldiers by using steel shutters:

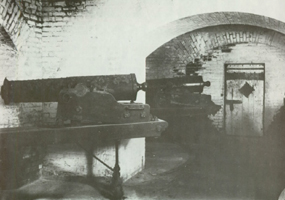

|

Dr. Mudd’s cell (door at right) and two 24-pound flank defense howitzers (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

“Joseph Totten was the chief of the Army Corps of Engineers. Joseph Totten designed Fort Jefferson and thirty other system forts. He also developed a way to protect these openings.

“The one thing you have to worry about is that opening. When the gas explodes, the shutter flings open and it is set up to close once the cannon fires. It is not spring loaded. It was very sophisticated for its time in the 1850s.”

Fort Jefferson’s primary use was a refueling and supply port for the naval fleet, but its design made it a powerful weapon of the sea. This type of weapon did not run itself, and the fort was designed to house 2,000 soldiers. The lives of military soldiers were an intricate part of the fort’s history. It was a hard way of living on Fort Jefferson, but for soldiers it was important to maintain national security of the Gulf Straits even if it meant living a life of isolation and suffering.

Soldiers did not have the luxury of electricity in the 19th century. By painting the ceiling of the case mates white, they created artificial light. It was just another way soldiers had to overcome disadvantages at Fort Jefferson.

“They had to paint the walls in the case mates white to make it look like there was more light. When these cannons are firing in battle this case mate gets very dark, so they needed light to see,” explained Mike Todd, a tour guide for the Key West-based ship Yankee Freedom II. The Yankee Freedom II provides daily tours to Fort Jefferson.

|

Company C of the 5th U.S. Infantry mustered and formed for inspection in May 1898 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

The life of a soldier was not easy. The intense heat and the isolation of the island were difficult for engineers and soldiers while the fort was constructed. According to Ryan, these conditions can be difficult for a person to handle:

“These young men that were out here … for them this is a very inconvenient place to be. You’re out in the middle of nowhere. It is very remote.

“You realize how vulnerable a human being is out here. Doing strenuous work. It is hot out here. You are reminded of how remote you are.

“The hardships soldiers experienced on the fort is best described in a collection of letters from Sgt. Calvin Shedd, a soldier from New Hampshire stationed at Fort Jefferson in 1862. His letters give a unique insight in the life of a soldier and the hardships he experiences at the fort. Shedd’s letters were written to his family and explained in detail the way of life in the Dry Tortugas.

On June 9, 1862, Calvin Shedd wrote ” …[I]t is tremendous hot here today. Two men died yesterday one was sick only 13 hours the other had been sick before … the lives of many of us will lay at the Doors of some of the Officers the Curses of the man against them are loud and deep.”

Shedd’s letters also describe the illnesses soldiers suffered on the island, along with the work they did constructing the fort. Each of his letters conveyed his urgency to leave the isolated Garden Key island and return to his family in New Hampshire.

|

Fort Jefferson’s Officer’s Quarters, no longer standing, in 1898 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

In the 1860s, the history of Fort Jefferson becomes one of imprisonment, illness and death. The fort was converted into a military prison when the Civil War started in 1861 and maintained a collection of Union prisoners.

In 1865, Dr. Samuel Mudd became the most famous prisoner to ever be at Fort Jefferson. He was accused of working with John Wilkes Booth in the assassination conspiracy of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Mudd and three other men accused in the assassination were sent to Fort Jefferson and, as fate would have it, his misfortune would save the lives of those who lived at the fort.

“All hope abandon, Ye who enter here!”

These are the words written on a door to a room in a cannon room called a bastion. It is a phrase that was written on the door of one of the rooms in which Mudd stayed. Ironically, the doctor would be the only hope for the soldiers when a severe case of yellow fever fell upon the inhabitants.

|

Barbette tier armament in May 1900 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

In 1867, a soldier returning to the fort from Cuba was sick and suddenly died. The only physician died a few days later. It was soon determined an outbreak of yellow fever found its way to the island.

Mudd was the only person who could stop the disease from killing the rest of the soldiers and prisoners. He did eventually eliminate the yellow fever and after spending four years at the fort, President Andrew Johnson pardoned him in 1869.

But yellow fever would find its way back to Fort Jefferson in 1873. Another group of residents returned from the island from Cuba and this time the yellow fever was so bad that 34 people became ill and 14 people died. NPS records claim the problem of this case of yellow fever is contributed to poor sanitation systems on the island. Records from naval officers and engineers differed on this claim, but records do show that sanitation at the fort was poor.

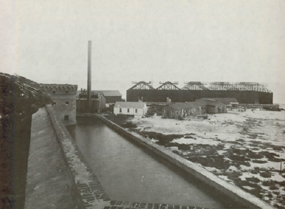

|

The Naval coal shed outside the fort on December 3, 1899 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

The sanitation problems soldiers faced are a problem for rangers and guests to the national park today. Currently the sewage and drainage systems are broken at the park.

Archeologists Margot Schawdron and Chris Lydick from Florida State University have been sent to the fort to fix the problem. It is a problem that has plagued this island before.

“Our job is to landscape the sanitation systems and fix them. Here are some diagrams … illustrations of how they have designed the drainage systems in the past,” Schawdron says as she refers to diagrams, which illustrate the old building plans of the engineers who built the fort.

It is a symbolic piece of history. A document of what engineers were thinking when they built this massive fortress to accommodate the soldiers. But it had its problems. The sinking of the fort in the 1850s because the heavy weight of the brick was too much for the coral island to handle. The sinking damaged the water-collecting cistern, and damaged the sewage system.

“The sewer lines will be updated,” Ryan says confidently. The archeological work and construction of a new sewage system is expected to be finished by Sept. 14, 2003.

“They had to stop working on the fort because of weight. They couldn’t work on these second tiers. They couldn’t put the guns up here. They put one layer of brick to make it look like it was done,” said Todd.

The combination of the yellow fever, construction problems and poor sanitation made it difficult to find a reason to maintain the fort as a necessary need for the military.

|

Soldiers in quarantine in spring 1899 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

Also a hurricane in 1873 caused severe damage to the fort’s incompleted structure.

The Navy abandoned the fort in 1874 and a large majority of the soldiers and prisoners were moved from the island. A small group of officers stayed behind with Army engineers to maintain minor construction on the fort.

In 1888, Fort Jefferson was used as a quarantine station for the sick. Its usefulness changed in 1908 when the fort was designated to be a wildlife refuge for loggerhead and green sea turtles. NPS took over maintenance the fort and it was named Fort Jefferson National Monument in 1935. It was re-designated the Dry Tortugas National Park in 1992.

The fort’s history has evolved from a military juggernaut of war to a sanctuary preserving the wildlife of the Dry Tortugas region. The history of Fort Jefferson may have destined itself for war. The fort’s walls did harbor isolation, suffering and illness for its former inhabitants, but it was located in a tropical paradise.

“If you weren’t stationed here, if you didn’t have to work here … I would say it would be a great place to bring a boat and go swimming for the day,” said Todd with a smile.

The purpose of the fort was for war, but its final purpose was completely the opposite. No cannon was ever fired out of an act of war.

|

The parade ground in 1867 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

The history of Fort Jefferson provides a window for those of the present to look into the past. Within the brick and steel walls, the inhabitants who once lived there tried to do anything they could not to remind themselves of the harsh conditions. They may have found escape from their surreal conditions within the walls.

Inside the parade grounds, grows a vibrant collection of trees. They have been there as long as the walls have stood and were the one thing the Army engineers felt would help the soldiers on the island deal with living in the Gulf of Mexico.

“This might sound strange, but we have some trees on the inside of the fort. Those trees were left here by the engineers when they built the fort. Because they understand by having a tree there was a sense of normalcy in this very surreal place,” Ryan explained.

Considering the conditions soldiers and prisoners endured at Fort Jefferson, trees became symbols of normalcy. It was a way of escape from an island they could not leave. Fort Jefferson’s story reminds us of hardships, isolation, illness and death.

Throughout this time, the trees in the parade grounds always remained. The trees are a reminder to all the inhabitants who lived at Fort Jefferson for 157 years. They are a reminder of hope.

|

| Image courtesy of Richter Library, University of Miami. |

Fort Jefferson: Facts and Figures

- According to the National Park Service 16 million bricks were used to construct the fort. Some reports state there could be up to 40 million bricks used in building the fort.

- Even though the fort is located in the middle of the ocean, it has a moat surrounding it. The moat was created to protect the fort from tidal waves and would be a physical obstacle if enemy forces landed on the island.

- The fort has two different colored bricks: yellow and red. The yellow bricks were placed before the Civil War and came from Pensacola, Fla. The red bricks were brought from northern states to the island during the war, when Fort Jefferson became a Union fort.

- The walls of Fort Jefferson are 8 feet thick and 45 feet high.

- The fort was designed to hold 400 cannons, but it only held a maximum of 89 cannons.

- Construction on Fort Jefferson lasted 30 years until it was abandoned by the military in 1874. The construction of the fort remains incomplete.

- The NPS has recently been granted $15 million toward repairing damaged brick and construction at the fort.

More information about the history of Fort Jefferson is available at the National Park Service Web site: http://www.nps.gov/drto.

For more information and images about 19th century life on Fort Jefferson and the Dry Tortugas National Park, visit the Calvin Shedd papers archive at Richter Library at the University of Miami, Coral Gables campus, on the Web at http://www.library.miami.edu/archives/shedd/site_index.htm.

|

| Fort Jefferson from the air in 1935 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and the National Archives). |

Comments are Closed