Stressed reefs in park suffer slow demise

HOMESTEAD, Fla. — Imagine the coral reefs, an underwater city of rock-like structures.

The staghorn coral sticks out in jagged shapes, with branches extending in every direction. A vast brain coral sits at the bottom, its surface covered by connecting twists and turns, while the coral fan looks like giant leaves, standing upright against the force of water. All these species can come in any color of the spectrum, captivating divers for years with their bright reds, blues and purples.

Now imagine them all void of color, bleached, as if someone had poured the cleaning chemical over an expansive portion of their population. Seems tragic, but it is very close to the truth.

| Click on the video at the right to see an audio slideshow about the coral reefs of Biscayne National Park narrated by park biologist Amanda Bourque and prepared by writer Laura Yepes. |

The reality of the corals is far from what many can imagine. The reefs are dying. And they are disappearing fast.

Matt Patterson, a coral biologist and the network coordinator for the South Florida/ Caribbean network of the National Park Service, estimated that around 60 percent of the delicate species has been destroyed by bleaching, one of the biggest threats to their survival. The process is caused by stress on the corals, coming from polluted and warming waters.

If people were to go out to see the barrier reef at Biscayne National Park or the Dry Tortugas National Park today, he said, they would see colorful specimens and fish living there.

But it is not as healthy as 60 or 50 years ago.

“You could be fooled because, unless you’re a scientist, you could think they’re healthy,” Patterson said.

Part of the reason for this apparent lack of awareness on the wellbeing and survival of the reefs is because it is an underwater ecosystem. The oceans remain a great mystery, and with scientists not being able to manipulate the factors surrounding these species, it is nearly impossible to know exactly what is harming them, and how it can be reversed.

| At right, two gray angel fish seen on the coral reef within the park (Photos courtesy of the National Park Service). Below, a pork fish swimming along the coral reefs. |  |

That is not to say that they are completely at a loss for what is going on with the corals. It is more of a confusion among a growing amount of threats. Patterson listed global warming, climate change, overfishing, and destruction through boats as some of the more serious ones, but the list is not exhaustive.

According to research by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the coral cover on many Caribbean reefs, which includes the system in South Florida, has decreased by up to 80 percent over the past three decades. Patterson said that reefs are slow-growing, maybe a few centimeters a year.

So, what has taken hundreds of years to make is being destroyed in just a fraction of the time.

And with that ecosystem disappearing, the chances of other wildlife disappearing increases as well.

More than 200 species of fish sustain themselves on the reef, feeding off of them and making their habitat there. This also helps the corals as well, because some fish, like the parrot fish keep the algae from suffocating the delicate structures, allowing them to continue receiving sunlight. It’s a cycle like any other ecosystem in the world, that affects much more than just the fish, but also the animals that feed on the fish.

“Everything is so dependent,” Patterson said. “It’s scary to think how everything would trickle out.”

One of the potential effects that could have a greater impact on the tourism industry in South Florida, which is known as the fishing capital of the world, is the depletion of big game fish. Both the growing scarcity of resources and overfishing are causing a significant decrease in the size and population of typically great catches.

One of the potential effects that could have a greater impact on the tourism industry in South Florida, which is known as the fishing capital of the world, is the depletion of big game fish. Both the growing scarcity of resources and overfishing are causing a significant decrease in the size and population of typically great catches.

It has become a conflict of interests, where the tourism industry needs both the preservation of the coral reefs so that people may still visit and to keep fishing largely available.

Park Ranger Gary Bremen said that one of the solutions Biscayne National Park is trying to implement that would balance out the interests is establishing a Marine Reserve Zone, part of the broader, proposed General Management Plan.

This would rope off 10,000 acres of the park’s waters, roughly seven percent of its entire area, where any type of activity besides just observing would be prohibited, including fishing and lobstering.

“Like any national park, we’re supposed to preserve and protect, but also allow for the enjoyment of these places,” Bremen said. “But the courts have said that when it is not possible to have those going on at the same time, if there is a conflict, the conservation takes priority.”

Death by a thousand cuts

Another way in which the park helps conserve the coral reef population is monitoring the damage inflicted upon them by boat groundings.

According to Amanda Bourque, a Biscayne National Park biologist and part of the damage assessment team, there are approximately 200 reported groundings each year, and 10 percent of those are on the reefs. Her team thinks that there are more accidents that go unreported, though.

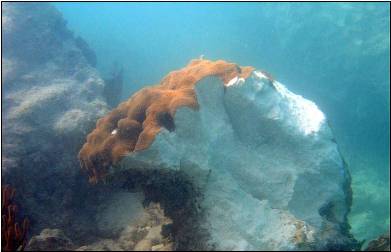

|

At left, coral with a large section missing (Photos courtesy of Amanda Bourque, National Park Service) Below, paint from the bottom of a boat left on a piece of coral. |

“The most common cause is human error,” she said. “People don’t pay attention to where they’re going or they never learn to properly navigate a boat.”

The types of damages that this can cause to the corals are geological and biological damage. Geological damages occur when the hard, outside layer of the organism is broken, exposing the soft part to more damage. Biological damage is when other organisms living in the reefs are hurt or killed. When a boat hits these structures, it usually causes both types of damages, Bourque said.

Under the Park System Resource Protection Act, employees of the park have the right to go to the responsible party of any damage and demand restoration. Whenever this happens, the involved parties usually settle for an amount based on what it would cost to restore the area.

That cost depends on how much was spent investigating the extent of the damages, plus what it would take to reverse them.

“The largest cases have reached one million dollars in repairs,” Bourque said.

Most are settled for less than $500,000, though. Boat groundings may not be such a huge factor in the deterioration of reefs as pollution and global warming because an accident will affect a small area. But with constant instances of groundings throughout the year, and adding up over the years, it’s causing what Bourque called “death by a thousand cuts.”

It is important for boat owners to pay attention to signs displayed in the waters warning of areas where they need to be careful, and also to be mindful of the navigational charts that point out appropriate routes for navigation, she added.

Raising awareness

Besides plans to restore marine life and monitoring activity in the park, the park rangers are also raising awareness about the importance of saving the coral reef ecosystem.

Bremen lets visitors know on his tours that while the reefs look beautiful and thriving they are actually in great danger and extremely vulnerable to human activity.

Bremen lets visitors know on his tours that while the reefs look beautiful and thriving they are actually in great danger and extremely vulnerable to human activity.

Bourque’s team started offering a course on preventing groundings that started in 2011, and they are expecting more to enroll next year. It might even become a requirement for people who cause damage, much like traffic school to an ordinary driver.

Patterson believes that people should become more civically engaged to call the attention of legislators to the need for action and funding.

He said that he worries that none of the political parties in the recent election mentioned much about the environment, a sign he takes to mean citizens must raise a call to action.

“I wonder if my grandchildren’s grandchildren will see what I saw as a child,” he said.

If You Go

- Biscayne National Park, 9700 S.W. 328th St., Homestead, Fla.

- To get to Convoy Point, where the Dante Fascell Visitor Center is located: From the North: From the Florida Turnpike: Take the Florida Turnpike south, to Exit 6 (Speedway Blvd.). Turn left from exit ramp and continue south to S.W. 328th Street (North Canal Drive). Turn left and continue to the end of the road. It is approximately five miles, and the entrance is on the left. Or you can also take U.S. 1: Drive south to Homestead. Turn left on SW 328th Street (North Canal Drive), and continue to the end of the road. It is approximately nine miles and the entrance is on the left. From the South: Traveling on U.S. 1 (Overseas Highway), drive north to Homestead. Turn right on SW 328th Street (North Canal Drive — first light after Florida Turnpike entrance), and continue to the end of the road. The entrance is approximately nine miles on the left.

- Convoy Point is open daily from 7 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. The Fascell Visitor Center is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The water portion of the park is open 24 hours a day. Adams Key, which is only accessible by boat is a day use area only. Prices vary. Trips depend on the number of travelers. To make reservations to go on snorkel trips or glass bottom tours to see the coral reefs go to http://www.BiscayneUnderwater.com

Comments are Closed