Sea levels increase, create new risks

Sea levels have increased steadily by one to two centimeters every year since 1900, but in the past decade this has increased to between three and four centimeters of rise a year, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“Earth’s climate is changing, with global temperature now rising at a rate unprecedented in the experience of modern human society,” according to the Arctic Impact Climate Assessment of 2004.

|

The shoreline at Cape Hatteras (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

These two international organizations have been bringing the problems of climate change to the forefront for years. Recently, organizations in the United States have begun research to determine what this means for our seashores.

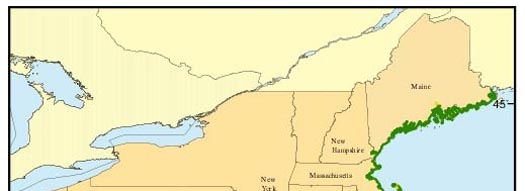

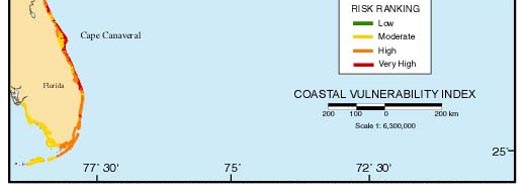

The Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) was created in 2001, in a partnership between the United States Geological Survey and researchers at Woods Hole Science Center in Massachusetts.

The CVI is used to determine the physical response of coastal environments to change in sea level. As well as which coastlines are going to be the most threatened.

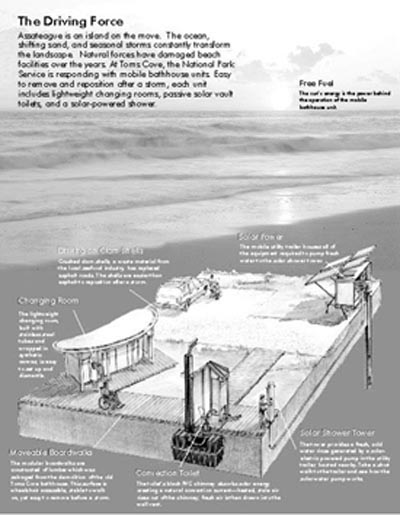

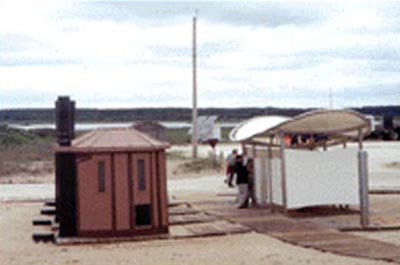

| Assateague Island National seashore has mobile boardwalks, changing rooms and bathrooms that can be moved in the case of a sudden sea level rise. These mobile structures are moved inland every winter (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy). |

|

The CVI is calculated by averaging six factors, geomorphology, coastal slope, relative sea level rise, shoreline erosion/accretion rate, mean tide range, and mean wave height, and then taking their square root.

Using this data, the national seashores that may be most vulnerable were compiled and are being carefully watched.

This rise in sea level has caused the water to begin to approach structures on the shores of many of the protected seashores listed in on the CVI.

Seashores, such as that at Cape Hatteras National Seashore in North Carolina, have already had to move structures.

|

The Bodie Island lighthouse, part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, has already been moved a quarter mile inland because it was threatened by sea level rise (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“The lighthouse was already moved from close to shore to around one-quarter of a mile back. In the long run, it will still be faced with more problems,” Megan Carfioli, natural resources manager of Cape Hatteras, said.

In a planning, environment and public comment from Cape Hatteras Superintendent Mike Murray, movement of other structures is discussed as well.

“The National Park Service (NPS) is considering relocating the Coast Guard Station and Life Saving Station on Bodie Island, at Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Dare County, N.C. This action is needed because the Coast Guard Station and Life Saving Station is about 75 feet from the Atlantic Ocean at high tide and is in danger of being destroyed by the eroding shoreline. Relocation will ensure the preservation of these historic structures.”

Despite, the necessity to move some buildings, sea level rise is more of a future problem with most national seashores.

Linda York, the coastal geologist in the National Park Services southeast Regional Office in Atlanta Ga., stated “sea level rise is viewed as a long term issue, but management plans that are currently being made are taking it into account.”

Assateague Island National Seashore in Maryland and Virginia has a few methods for dealing with the rising sea levels that occur during the winter. Multiple buildings that are near the shore during the spring can be moved so that in the winter, when the water level rises, they won’t be damaged.

| The mobile bathrooms on Assateague use solar power and gravitational pull to provide water and energy. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Dept. of Energy). |

|

When asked if he thought they would be a reasonable solution in the future to sea level rises, Mike Barrett, head of maintenance at Assateague Island, said that “moving the structures was no big deal, but the larger issue is getting the public to the new location and dealing with the logistics of that, I don’t really know if they would make sense for something like that.”

Funding also factors into what can be done to deal with buildings in the path of the rising sea level.

“Budget constraints mean that we usually wait for buildings to be damaged or aged before we begin to replace them,” said York.

This would make it difficult to begin installing mobile buildings without a need for them, as the threat of sea level rise is not a pressing issue at the time, he said.

Michael Bilecki, chief resource Manager of Fire Island National Seashore on Long Island in New York, another seashore on the CVI, agreed, stating that “it is the National Park Service’s policy to let nature run its course, we are doing studies on sea level rise, but really we just have to let what is going to happen happen.”

Most parks are more currently concerned with storm impacts.

Sea level rise has been taken into account, though. Research is currently being conducted at Fire Island National Seashore which studies bayside marshes and whether or not they are keeping up with the rising sea levels, and if they will be able to keep up with the projected rise.

|

Boardwalks such as these, that are close to the shoreline will eventually become threatened by sea level rise, and in the end could be covered by water (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

According to Bilecki, “global climate change has caused a rise in sea level and the study says that the marshes won’t be able to keep up.”

Parks are going to have to deal with whatever happens though; interfering with the sea level rise is interfering with natural processes, and could create more problems than solutions.

The best way to sum it up may be in the words of Megan Carfioli.

“It’s going to happen whether we like it or not,” she explained. “It’s a challenge with no real answer.”

|

| The Coastal Vulnerability Index is an analysis of how threatened certain coastlines are to sea level rise. This measurement considers wave height, geomorphology, coastal slope, relative sea level rise, shoreline erosion, and mean tide range (Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey). |

Comments are Closed