Climate change impacts Alaska parks

National parks in Alaska are responding to the multifaceted issue of climate change through local programs and National Park Service (NPS) programs, monitoring existing changes and utilizing scenario planning to prepare for probable effects of climate change in the future.

“The Arctic is more sensitive to climate change than perhaps any other place on Earth,” said Terry Chapin, a professor of ecology with the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.

Alaska is home to 23 national parks, monuments, preserves, historical sites and other NPS sites. Each park is different than the other, varying not only on the natural features of the land, or the water, but also on the geographic location of each. Climate change affects each park in its own manner precisely because of these different varieties of terrain.

| The Juneau ice field in the coastal mountains of southeastern Alaska provides an image of what most of southeast Alaska looked like during the late Wisconsin glaciation in the past ice age (Photo by Tom Ager, courtesy of the National Park Service). |  |

“Warming in the interior has risen seven degrees in the last few decades and this is where we’re located,” said Kris Fister, Denali National Park public affairs officer.

The media have often covered Arctic climate change in the last decades with alarming articles on the dire effects on tourism and the environment. Most of this coverage, however, is convoluted precisely because Alaska is so varied and each area has its own effects to climate change.

“Glacier Bay is in the south,” said Allison Banks, Glacier Bay outdoor recreation specialist. “These glacier fields are different than changes in the Arctic Circle.

Holly Howard is the seasonal interpretive ranger in the Western Arctic National Parkland, which is the administrative unit for four national parks. The office is located in the Arctic, and suffers greatly from the most commonly discussed climate change of the Arctic; the melting ice caps.

“We had to build a seawall to keep the water from coming inland,” said Howard.

Guy Adema is the natural resource team manager in the central office in Alaska, overseeing the management of natural resources in each of the parks, including climate change. He said that things are changing, and that is why NPS is focusing so much on the monitoring.

Jonathan Jarvis, director of the park service, said climate change is highly significant for the future of national parks sites.

The national parks in Alaska are experiencing shifts in vegetation, habitat, and consequently, wildlife distributions. Adema said that large areas are transitioning from frozen tundra to a shrubby landscape in shockingly short periods of time.

Howard was recently involved in installing climate monitoring stations in the four park units. They are part of the Arctic Network Inventory and Monetary Program (ARCN), which she said is meant to build a baseline so future climate can be compared to previous climate, and we can better understand what is going on “out there.”

Banks sees an alternate type of monitoring in Glacier Bay; in fact, she emphasizes the fact that one of the main driving forces for the creation of it was for climate and glaciology scientific research. She explains the multifaceted notion of climate change, what can be accounted for human interference, or what is simply a natural environmental evolution.

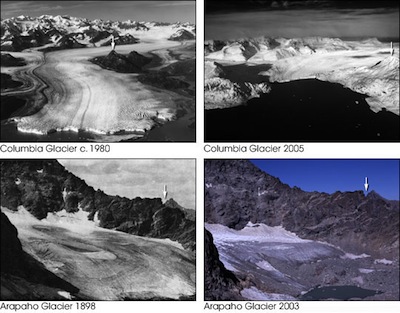

| The effects of climate change on Columbia Glacier and Araphao Glacier. (Photos courtesy of Tad Pfeffer and the National Park Service). |  |

“One of the reasons Glacier Bay was established was to see these changes,” said Banks. “Glacier Bay has always been changing and it has been difficult since the beginning to tease out what causes these dramatic changes.”

Adema speaks of the subjectivity of the word dramatic. To people in the scientific community, like himself, dramatic changes are occurring over a time period that others would consider a long time, making these effects not so dramatic.

“There is clearly change happening just not on the time scale people are thinking of,” said Adema. “As a whole, I think the climate change [in the media], for me, has probably gone further than it really is.”

Fister explained how the main attraction in Denali is Mt. McKinley, the highest peak in the United States. Within the park, there have not been major effects of climate change in its main attraction nor elsewhere, but that monitoring the environment is essential.

“We haven’t gotten to extreme biological effects yet, but we’re monitoring,” said Fister. “What we do about the effects will be the biggest conundrum.”

Adema explained the relatively new concept of scenario planning as a tool to calculate and manage futures with high uncertainty and lack of control based on the current data retrieved from monitoring efforts throughout Alaska’s national parks.

|

Johns Hopkins glacier in Glacier Bay National Park. (Photo by Commander John Bortniak, courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“When all the factors are beyond our control, we will have to determine a solution within these restraints,” said Fister.

This is also done through Scenarios Network for Alaska Planning (SNAP), which is a collaborative organization linking the University of Alaska, state, federal and local agencies, and non-governmental organizations.

According to the SNAP website, the primary products of the network are datasets and maps projecting future conditions for selected variables, and rules and models that develop these projections, based on historical conditions and trends

“The key word is unpredictability, what had been the norm has now changed,” said Howard. “The change is real, people in other places may not feel it, but the people here [in the Arctic] are living it every day.”

In fall 2010, the National Park Service published its Climate Change Response Strategy, which gives an overview of how it will address climate change.

Under the section Adaptation, scenario planning is a main concept in which NPS concludes that “scenario planning can help managers explore assumptions, test hypotheses, and ultimately develop robust strategies and actions to manage the uncertainties of climate change.”

The application of scenario planning in Alaska national parks will be able to address the uncertainty to which Howard speaks. There will be data of past and current climate changes and its effects in order to provide statistical information and plausible scenarios based on the statistical analyses and data.

Comments are Closed