Climate change brings impact to parks

Thousands of spruce bark beetles, each around the size of half a Tic-Tac, can be found scurrying along tree branches in Alaska’s Denali National Park. Together, they all gnaw their way through the bark until the tree is left skinned. Unprotected, white spruce trees are dying at an alarming rate.

Fires blaze through national parks in the Southwest, crackling as they swallow every tree in their path. Forest fires get trapped in a ferocious cycle—higher temperatures causing fires and fires letting off smoke and pollutants that lead to even higher temperatures.

Within the last century, the environment across the globe has faced destruction that is rapidly gaining intensity.

But perhaps the most dangerous effect of climate change isn’t hurricanes blowing over skyscrapers or an overpopulation of insects, but rather land that is disappearing completely.

Glaciers and the snow that covers them have done a vanishing act in the last century. Denali National Park in Alaska and Glacier National Park in Montana clearly display largely puddled landscapes. At the same time, with the north and south of the globe liquefying, the coasts are creeping inward. Biscayne and Virgin Islands are expected to be the first National Parks to drown.

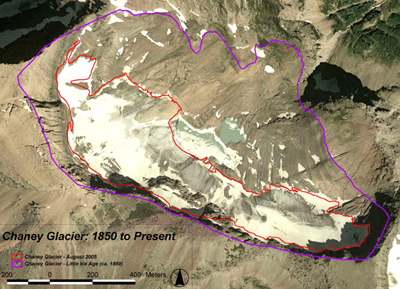

| The image at right shows changes in size of Chaney Glacier at Glacier National Park over the past 150 years (Courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey). |  |

“We’ve certainly seen loss in glaciers,” Kris Fister, spokeswoman for Denali, said. “This impacts everything from micro-vertebrates to spring snow melt to little critters, in terms of habitat changes.”

In the short-term, melting permafrost can mean smaller glaciers and bigger lakes. Contrary to popular belief though, the National Parks Conservation Association says that too much thawing can lead to lakes disappearing. Many of these bodies of water are on top of underground collections of small rocks or sand. As more water accumulates, it gets heavier, makes contact underground and gets sucked in. The lake disappears.

“And then we’re seeing changes in snow cover, which leads to vegetation changes,” Fister said, “and therefore, changes in wildlife populations because of community types will change what can live there.”

Glacier National Park is seeing many of the same changes as Denali, due to their similar landscapes.

“Because of the melting of the glaciers and the warming of the waters, we’re finding some species—especially aquatic species—are becoming more rare,” said Ellen Blickhan, acting public affairs specialist at Glacier National Park.

The protected Nelchina caribou in Denali live best in the tundra among spruce forests. But as temperatures climb, the tundra is disappearing in the south where it’s warmer. Spruce trees are being eaten alive by spruce bark beetles, which have overpopulated in warmer temperatures. These endangered caribou are moving north, where hunting is allowed.

The National Parks Conservation Association predict that 90 percent of the tundra in Alaska will be gone in 2100 due to climate change.

The first step for the national parks suffering from melting landscapes is to monitor the change closely.

|

At left, Glacier National Park today. Over the years, the amount of snow has greatly decreased (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). Below, rising temperatures will not only flood island national parks, but a few degrees difference will kill coral. This will completely change ecosystems in tropical oceans (Photos courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“We have basically a lot of temperature and precipitation stations, Fister said. “We look at annual average temperatures and the precipitation that has increased and the evaporation that has increased.”

The U.S. Geological Survey has taken Glacier National Park on as one of their research sites. It is one of their main sites for their Climate Change in Mountain Ecosystems project.

“We have our glacier field stations that are doing a lot,” Blickhan said. “USGS folks are the ones that are finding a lot of really interesting information.”

Glacier monitoring is one of USGS’s main focuses and they use multiple methods to get accurate results. First, they measure the mass of the glaciers and can therefore tell how much water was gained or lost throughout the season. They also take area measurements to see how much the glacier is shrinking. They measure the temperature of the water that is outflowing from the glaciers to know when it changes. Lastly, they take a lot of satellite and regular photographs to monitor changes in shape or composition.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that by 2030, Glacier National Park’s glaciers will have disappeared.

The National Parks Conservation Association is coming up with ways to protect what they can while everything shifts.

In Alaska, by monitoring the Nelchina caribou migration into hunting zones, NPCA is able to rezone to protect them. They are also taking measures to try to slow down climate change, like demanding control on state carbon emissions and helping rural towns become more energy efficient.

The effects of thawing glaciers that are seen in the North are only half of the problem. While melted fresh water begins to flow into the ocean, sea levels all throughout the coasts rise. This threatens all people and organisms on the shore, but they can shift their settlements inward.

Unfortunately, this is not a possibility for islands. As sea levels rise, they will go underwater and the environmental occupants won’t have anywhere to go. Biscayne National Park and the Virgin Islands National Park are two of the most threatened.

Most predictions by scientists say that all of South Florida, the Florida Keys included, will be under water in less than a century.

The National Parks Conservation Association is working to prevent too much damage, with places like the beaches sea turtles nest on in mind.

The National Parks Conservation Association is working to prevent too much damage, with places like the beaches sea turtles nest on in mind.

Pressuring the state to implement cleaner energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels is on the list to prevent rather than protect.

Since this hasn’t been overly successful and because so much of the damage that has already been done is irreversible, they’re also working to plan for disaster.

One of the ideas is for the national parks to attain more protected land further away from the coast. Then, the disappearing coast could link with the new land and the animals could migrate inland to survive. Protecting areas of the ocean would also allow marine animals to swim upwards to cooler water.

Unfortunately, very fragile ecosystems, like the coral reef would still die. A change in just a few degrees will kill coral, which will then harm all the fish that live there.

“I spent two years studying coral reefs,” Alanna Mitchell, author of Seasick, a book on global warming and the oceans, said. “I wouldn’t have done it if I didn’t connect with them and feel the passion.”

Much of the excess carbon dioxide floating around, that causes the greenhouse effect, is absorbed by the oceans. This poisons them, killing fish and decomposing shells.

Ecologists are looking into replacing the plants in the ocean that could not survive warmer temperatures and carbon dioxide. This would be an attempt to bring the area back to normalcy but probably only serve as a temporary fix.

The melting and flooding of national parks seems to be unstoppable since the damage to the environment has already been done. Politics and money tangle measures that could have been taken to stop climate change. Although unsure what will happen exactly, specialists from all over are working to keep the national parks in existence.

For more information on the national parks and climate change, visit http://www.nps.gov/climatechange.

Comments are Closed