Library preserves Kennedy’s legacy

BOSTON— Each deserving American president is granted the privilege of a library in his honor once his term is finished.

Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy’s rival, Richard M. Nixon, are among the revered figures for whom libraries across the country were named. In accordance with this patriotic tradition, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in South Boston, near downtown, is a tribute to the life and political service of one of America’s most beloved leaders.

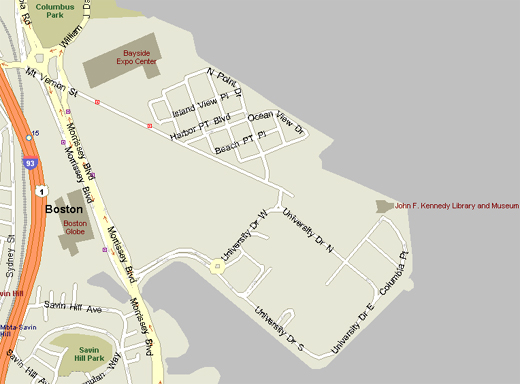

After taking Boston’s underground “T” train to the U. Mass ( University of Massachusetts) Boston stop, a shuttle conveniently awaits museum-bound passengers for an eight-or-so minute ride to the monument.

|

The Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum building has open space overlooking Boston Harbor, such as room in the pavillion (Photo by Shira Strassman). |

Upon arrival, a massive white structure appears with its vast planes and edges forming angular shapes that extend upward, piercing the cloudless sky.

Inside, ticket counter and information booths have attendants behind each station who are available to answer queries and sell tickets, respectively.

The first exhibit one passes through, before entering the main part of the museum, is a temporary exhibit called “A Journey Home—John F. Kennedy and Ireland.” It is chock full of unique memorabilia from the 35th president’s politically purposed yet sentimentally charged trip to Ireland, the birthplace of his eight grandparents.

Featured are original letters of welcoming and appreciation to Kennedy from Irish politicians during his June, 1963 expedition. Also displayed is a telegram from then Irish president Eamon de Valera, and gifts from his Irish hosts including a gilt silver chest, goblet, and Waterford crystal vase.

A photograph of Irish nurses with outstretched arms swooning over the visiting American president is reminiscent of the way the romantically unavailable husband of Jackie Onassis was received on the home front, and confirms the White House darling’s universal sex appeal.

| The simple entrance to the library and museum (Photo by Shira Strassman). |

|

A neighboring auditorium provides seating for a few hundred visitors to view an introductory video on the life and political times of JFK. Beginning with his acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, the film proceeds to enlighten viewers with “The new frontier”—a set of challenges and uncharted territories like science and space which the president willingly faced during his trying and accomplished term.

In a clip, Kennedy lectures about “the mediocrity of the past” and his visions for improvement in a time that required qualities like “imagination, courage, and perseverance” in a U.S. leader.

The movie briefly documents the U.S.’s entry into World War II and other profound events during his lifetime, while providing a glimpse into JFK’s background and upbringing.

His story starts with the tales of an ambassadorial father and a soldier brother who tested the turbulent political and military waters before he ever did. It continues with his degree-seeking days at Harvard University, his race for the U.S. Senate, and trails his successful climb up the political ladder. The film concludes with his confident presidential campaign promise: “And we shall win.”

After learning from the video that JFK had all the markings of a political powerhouse to-be, so begins the museum’s journey back in time with the campaign exhibit.

|

Campaign buttons from the 1960 election are on display (Photo by Shira Strassman). |

The theater’s exit leads to a door. With one push, you are transported back in time to an era of buttons, flags, posters and bumpers stickers all screaming slogans of political persuasion. Authentic examples of these are for show.

“Kennedy for President” is among the catchphrases once used to bring him into office.

And as the Kennedy ticket rivals the Nixon one, a thick air of contention fills the space inside the red, white and blue-drenched walls. A never-ending sea of pamphlets and signs are overwhelming.

As you walk, you feel as though you are riding the campaign trail, which ends cathartically in Kennedy’s victory speech. Copies of 1960 Newsweek and Time magazines capture the newsworthiness of the Kennedy-Nixon election.

Different smaller off-set exhibits depict more specific aspects of the campaign and the lifestyle of the time. In one room, an antique television plays a pro-Kennedy ad; in another, a period radio station bustles with voices on topics surrounding the election.

From what appears, the swarm of JFK propaganda was a success. With Kennedy’s straight-toothed smile and all-American persona, it is easy to see why the American public chose this face of optimism over Nixon’s unappealing, sinister one.

|

A replica of the stage and set for the televised presidential debates in 1960 (Photo by Shira Strassman). |

The campaign commotion culminates in a display of election poll tallies, complete with blue and red state plaques and their representing percentages. After describing the Kennedy win, the theme transitions into inauguration and then presidency exhibitions which both highlight his subsequent term in office.

Vietnam mayhem, with maps and news releases; Metals and awards given to the late president mark milestones in his career, like Pope Paul VI’s 1963 giving of a La Pieta replica to the president. Photographs of the Peace Corps which Kennedy founded adorn the walls in memory of Kennedy’s push for America’s contribution to global development.

In the “Handmade and Heartfelt” section, gifts from renowned figures around the world are present. An Indonesian puppet given by President Achmed Sukarno in 1961 is among the relics left in tact.

JFK may have been spoiled by worldwide generosity during his presidency, but don’t feel sorry for the First Lady of the period; Jackie was hardly neglected. In fact, sparkling jewels from King Hassan II of Morocco are encased here, perhaps so that onlookers don’t pity America’s former life sized Barbie doll.

The museum is open to student groups for field trips, which are guided by museum staff. One group visiting on the last Friday in March was comprised of about 30 elementary schoolers from the local Quincy School; the children each wore name tag stickers. For the most part, they were mentally engaged in their tour, yet clearly were further removed from the events of JFK’s life than their parents or grandparents would predictably be.

One student shyly admitted that the museum was only “a little” interesting: a testament to his youth, or even perhaps to his disinterest in the life of a president with no detectable effect on his generation.

Entire sections are dedicated to JFK’s promotion of the U.S. space program and furtherance of the civil rights movement, with a special segment called “Seeds from Segregation.”

| In addition to its historical displays, the library and museum offers stunning views of the harbor (Photo by Shira Strassman). |

|

Further inside, a replica of the oval office contains his original desk—all behind a rope, of course. A student tour guide explains that behind the desk is a secret door where the Kennedy children once played hide and seek. Beside it is also the original rocking chair where JFK once rocked to soothe his back, which was often achy after his army experience.

The museum pavilion, accessible from a staircase that joins it to the main lobby, is a tall glass wall behind scaffolding. It provides a view of Boston Harbor, which Kennedy loved, and is outlined by podiums where museum-goers can read some of his quotes—mostly on the qualities of democracy, inspiration morality and sacrifice—which he sought to uphold.

One floor up, on the main level, the “JFK Café” serves a variety of sandwiches and salads, coffee and cold beverages, with a beautiful view of the harbor available at its window-side tables. Just next door to it, the museum gift shop sells everything from books on the late president to clothing, and more.

Cloistered in a restrictive upstairs location where only approved researchers may enter, is the Hemingway Room. There, right beside the annals of Kennedy literature lay photocopies of Hemingway’s original manuscripts. (The originals are also owned by the JFK Library but can be touched by only a few special hands.)

The room itself is fairly small, and is decorated with the aim of rejuvenating the spirit of Hemingway. It recreates the atmosphere in which the writer once wrote his great works in Cuba before he fled. There are couches, an animal hide rug; also real letters, a diary and other memorabilia.

As for the connection between the writer and the president whose memories are honored in the same building, Hemingway and Kennedy coincidentally shared a friend: William Walton. The same man who served as an informal advisor to Kennedy was in fact a friend of Hemingway’s wife Mary, who retrieved her husband’s belongings in Cuba with his help, according to JFK librarian Stephen Plotkin.

“She piled stuff onto a shrimp boat and got it back to Florida, put it in a vault, and later gave it to the government (who eventually gave it to the museum),” Plotkin said.

Behind the ticket counter, saleswoman Ann Kenney and her co-workers sell around 250,000 passes to the museum each year. Why? “It’s a must-see, especially for older people,” Kenney said. “They lived through Kennedy’s life, so it means quite a bit [to see the museum].”

Kenney describes JFK’s appeal as being due to a few key factors. “He was charismatic, young, had a beautiful family…very intelligent, spoke very well,” she said.

Her words ring true, as Kennedy may have been, among other things, the most eye-catching man ever to grace the oval office. A combination of energy and charm are what drew many fans—at least the female ones—to adore the Boston native.

The JFK Presidential Library and Museum demonstrate that Kennedy’s legacy has indeed transcended ethnic, cultural and generational boundaries– perhaps for all the reasons noted above and more.

Walking through the museum, it is almost as if Kennedy is alive today. And that sentiment is no accident.

The non-profit Kennedy Foundation and the federal government, both of which helped to fund the museum, decided upon its inception that “They want to reflect on his life, not his death,” Kenney said. It is in this way that the memory of John F. Kennedy lives on.

If You Go

- Address: The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Columbia Point, Boston, Mass. 02125.

- Phone: 866-JFK-1960.

- Hours: Seven days per week from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Closed New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day .

- Admission: Adults $10, seniors and students (with valid college ID) $8, ages 13-17 $7, children 12 and under are free.

- If you are driving: The Library and museum are located on Columbia Point in Boston, close to route I-93. Parking is free for museum visitors.

- Public transportation: Take the MBTA Rapid Transit, Red Line (any red line train) to JFK / UMASS Station. There is a free shuttle bus marked with “JFK” to the Library every 20 minutes beginning at 8 a.m. and running until museum closing.

- Accessibility: Wheelchairs are available at the Visitor Admission Desk on a first come, first served basis. Video presentations in the museum are captioned for hearing-impaired visitors. American Sign Language interpretation is available with advance notice. Call 617-514-1569 for more information.

- Exhibition note: The Ireland exhibit will be featured until Feb. 28, 2007.

- Questions? Contact the museum administration at 617-514-1541.

Comments are Closed