Confluence conflict: Protect or develop?

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — Turquoise water kisses murky, emerald water and the sun scorches the canyon’s abyss. The only audible sound is the rush of the two rivers colliding, the hum of nature in the secluded depths of the Grand Canyon.

This meeting place about 90 miles north of here, where the Little Colorado River and Colorado River combine, is an unmatched ecosystem and the crux of cultural tradition for Native American people: This is the Confluence.

| Click on the video at the left to view a narrated slide show about the Grand Canyon Escalade Project prepared by writer Marissa Vonesh. |

The Confluence has become a point of contention for the Navajo Nation. The Nation is the largest reservation in the United States, settling on more than 27,000 square miles within Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. The Nation is divided into 110 Chapters and is semi-autonomous having its own executive, legislative and judicial branches.

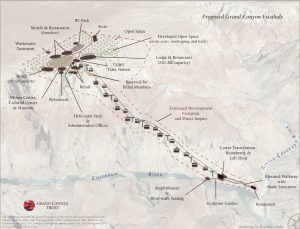

Currently, members of the Navajo Nation Council are working with a private development group, Confluence Partners LLC, based in Scottsdale, Ariz., to construct a tramway into the Grand Canyon. According to the developer’s proposed plans, the project – dubbed the Grand Canyon Escalade – will expand to more than 420 acres and include an eight-person gondola tramway from the rim of the canyon to just above the Colorado River, leading to an elevated river walk complete with a food pavilion and amphitheater.

Furthermore, on the rim, Confluence Partners plans to build a discovery center that will feature themed cultural and historical entertainment. It is also slated to provide shopping and dining experiences, create lease sites for hotels and offer opportunities for local Navajo craftsmen to generate sales revenue.

The tourist mecca would provide an opportunity for people to see a vulnerable, secluded part of the canyon, regardless of physical ability, which is usually a necessity with the Grand Canyon, and a unique look into the cultural background of the Navajo people.

The Grand Canyon Escalade would be located on the Eastern Rim of the Grand Canyon and on the Western portion of the Navajo Nation. The project was approved by the land’s local Chapter, the Bodaway-Gap, on Oct. 3, 2012, on the basis of providing economic opportunity.

Economic Hope

The Grand Canyon Escalade would provide a desperately needed economic option to the impoverished lands of the Navajo Nation. The region has been subject to the Bennett Freeze, a policy that froze development due to a land dispute between the Navajo and Hopi tribes.

Introduced by Bureau of Indian Affairs Commissioner Robert L. Bennett in 1966, the Freeze halted even basic home reparations, leaving hundreds of families in dire living conditions. In 2009, President Barack Obama formally repealed the Freeze.

“Native Americans living in the Bennett Freeze region reside in conditions that have not changed since 1966,” according to legislation that repealed the Bennett Freeze. “Only three percent of the families affected by the Bennett Freeze have electricity, and only 10 percent have running water.”

The region is not the only area in the Navajo Nation in need of economic renewal. According to the Navajo Nation’s Division of Economic Development, 43 percent of the Nation’s population lives below the poverty line. A large majority of the Navajo Nation relies on Peabody Energy’s Kayenta Mine and the Navajo Generating Station (NGS) power plant for jobs. In fact, 51 percent of annual revenue is attributed to mining.

With the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan of 2014, coal plants are required to reduce carbon emissions; therefore, it is likely NGS will have to close one of its three units. At this point, it is necessary for the Nation to invest in alternative economic options.

Confluence Partners LLC, promoted by developer R. Lamar Whitmer and former Navajo President Albert Hale, is promising more than 3,000 jobs as a result of the development.

According to the project’s website, the project is intended to “bring diverse groups of Navajo people together for a common goal: to create opportunities while maximizing human and natural resources.”

Furthermore, Confluence Partners estimates the Grand Canyon Escalade will create $70 million in annual local payroll and an estimated $90 million in annual revenue for the Navajo Nation.

Concerning Discrepancies

To many, however, the Grand Canyon Escalade is an empty promise, contemptuous traditional beliefs and a desecration of the Grand Canyon. A resolution to the master agreement was posted in August 2016, sponsored by Benjamin Bennett – the vice chair of Resources and Development Committee and delegate to the Navajo Nation Council.

The resolution asks the Navajo Nation to pay an initial $65 million for the offsite infrastructure of the tourist attraction, such as the roads, electricity and water, and holds the Nation permanently responsible for all offsite maintenance. The Escalade legislation additionally allows the pre-approval of business site leases without the review of Navajo offices and agencies, overrides prior resolutions – such as the 25 percent of profit returning to the Bodaway-Gap resolutions – and violates the Inter-Tribal Compact with the Hopi Tribe that requires consultation within cultural areas.

Furthermore, the agreement incorporates a “no compete” clause, which forbids all business within 15 miles of the project and within 2.5 miles along either side of the road to the site; therefore, traditional craftsmen cannot sell their products to passersby and local entrepreneurship is out of the question.

Although attempts to talk to representatives from the Confluence Partners LLC for this story failed, the developer’s website claims that the Navajo Nation will ultimately own 100 percent of the Grand Canyon Escalade, yet it fails to mention the formative years of the project.

According to the master agreement, the investment partners would own all the profits within the first 50 years and the Navajo Nation would only receive 8 to 18 percent of gross revenue depending on attendance levels. Furthermore, the agreement waives various Navajo laws and holds the Nation responsible if the project were to fail.

Environmental Damage

Other issues with the proposed development include environmental concerns, such as light pollution, waste removal, traffic, the extraction of river water and the protection of the endangered humpback chub as well as fragile plant life in the canyon.

The Navajo Nation Trust Land Leasing Act of 2000 authorizes the Navajo Nation to conduct business site leasing without subsequent federal approval. The Act, intended to spur development in the Bennett Freeze area, allows the Nation to forego federal inspection, one being environmental. Confluence Partners LLC claims it will undergo “tribal environmental review,” but there is no promise as to how the environment of the Grand Canyon would be protected in the process.

“It’s a battle to the death, right now. There should never be a tramway,” Kevin Dahl, senior program manager for Arizona at the National Parks Conservation Association, said. “[Confluence Partners] is a private entity, they can say whatever they want. Whatever they say they don’t have to conform to.”

The line that defines the Navajo Nation and Grand Canyon National Park is also unclear at this point. The developers claim the project would solely be on private land; however, the Escalade has the potential to intrude into the park during development. Confluence Partners has not commented on a plan to prohibit invasion into the park.

“Right now the proposed project is all on Navajo land,” Emily Davis, public affairs specialist at Grand Canyon National Park, said. “As of now, the park is relying on the process that the Navajo Nation and the U.S. government has in place before it does anything.”

A Wellspring of Life

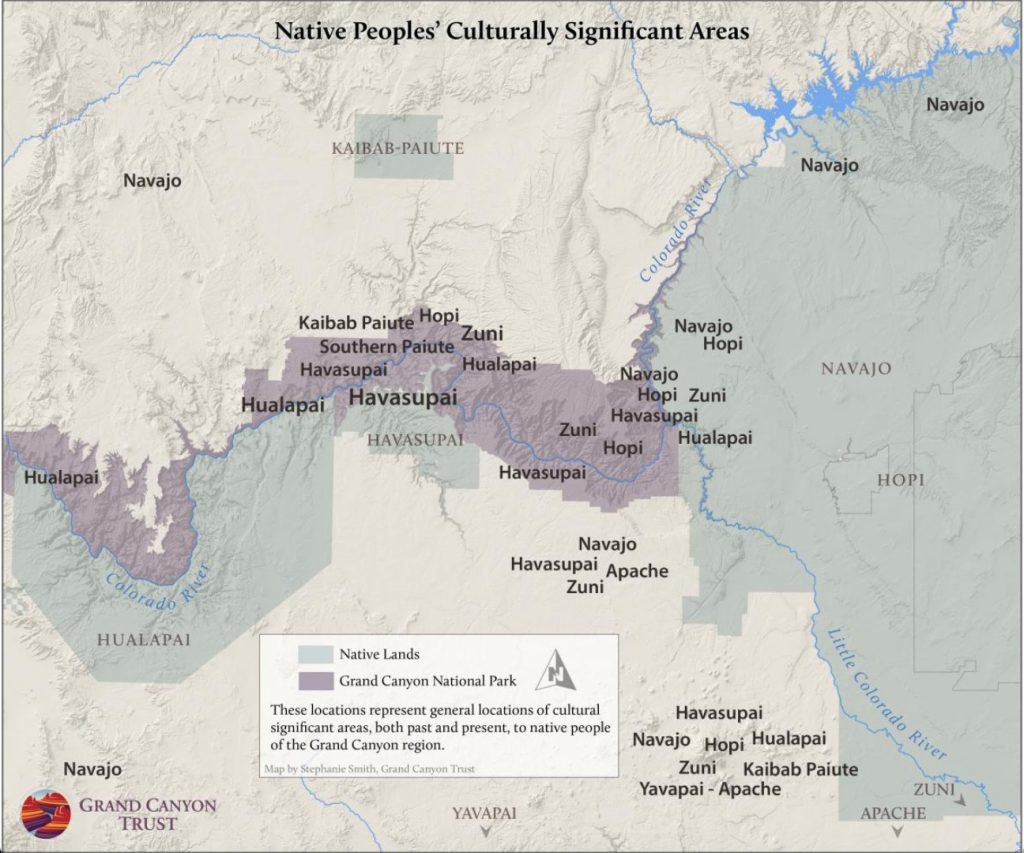

The main concern of the Grand Canyon Escalade is its infringement on sacred Native lands; the Confluence is considered sacred by Navajo, Hopi and Zuni traditions. To the Navajo people, “anywhere where rivers come together is sacred,” according to Jason Nez, a Navajo archaeologist. “Life comes from these places in the form of the froth, which is the first form of life in the first world according to Navajo tradition.”

The Navajo people living in the region proposed for the development have organized as Save the Confluence. According to this group, the site is vital for religious purposes: “The air, space, water, plants and land are very much alive and have beating hearts like ours. We take our prayers to the Colorado and Little Colorado River for blessings.”

The Navajos’ Holy Wind People occupy the Confluence and there are various holy sites along the rim that would be destroyed as a result of the Escalade.

For the Hopi, the Confluence is a part of the holy Salt Trail. In Hopi tradition, humans emerged from a salt dome that is located near the intersection of the two rivers. Pilgrimages and ceremonies are performed annually in and around the Confluence region. Furthermore, the Grand Canyon (Ongtupqu) is a revered space as a whole. The Zuni people likewise believe life emerged through a place not far from the Confluence.

To the Indigenous peoples of the Southwest, the Confluence is a common area to pray and a traditional resting place for ancestors.

The Hopi Tribal Council, Zuni Tribal Council and the All Pueblo Council of Governors have each submitted official oppositions to the Navajo Council, arguing against the development of the Grand Canyon Escalade.

“Sacred places like [the Confluence] are important to the balance of the world. By desecrating it ourselves, we unbalance the whole world. Families are already divided, communities are already divided and these divisions will spread to tribes which are currently united and working together,” Nez said.

The Confluence Partners LLC provides evidence on its website that no sacred land will be harmed by the construction of the Escalade. The developers parallel the proposed project to the activity of recreational hikers and rafters who travel to the Confluence, expressing the land would not be harmed more than it already is.

With an expected 10,000 tourists visiting per day, there is no question the site will be affected in some way. The natural landscape so vital to indigenous traditions will be changed, noise and pollution will increase and visitors will inevitably travel off-trail – potentially adding to the ruin of sacred prayer sites.

Proposal Slowing Down

The pursuit of profit or protection has led to a divide on the Navajo Nation. Although the original development plans were passed by the Bodaway-Gap Chapter, the Grand Canyon Escalade’s revised plans have to be reviewed by four committees and approved by 16 of the 24 Navajo Nation delegates on the council.

On Oct. 5, 2016, during the first meeting that dealt with the proposed bill, the Navajo Nation’s Law and Order Committee unanimously turned down the Escalade Bill by a vote of 4 to 0. The main concerns of the proposed development included the Nation’s ability to pay $65 million, the bill’s failure to address the grazing permit owners who live on the planned site and the issue of sustaining the earth-based Navajo faith.

Still, there is no answer as to how the developers will retrieve water for the project and how the no-compete clause fosters the economic welfare of the Navajo people.

Questions about the moral character of both Whitmer and Hale have been raised and opponents to the project claim Bennett has no reason to support a bill in an area he is not from. Nonetheless, the Confluence Partners addresses its “outside” infringement by holding onto its partnership with the Navajo Nation Hospitality Enterprise, current owner of two Quality Inns on the Navajo reservation and the Navajo Travel Center. When the Enterprise was contacted for comment on the development, the receptionist claimed, “we are not allowed to answer any questions on the topic.”

The bill will make its way through the Resource and Development, Budget and Finance and Naabik’iya’ti’ Committees before it reaches the council. The developers and Resource and Development Committee have scheduled the next meeting at the Bodaway-Gap Chapter on Dec. 13.

Uncertain Future

There is no prediction as to what the Navajo Nation will decide to do. The site is in dire need of economic attention and no real plans have been proposed to help alleviate the poverty aside from the Grand Canyon Escalade. The Confluence Partner’s motto, “our land, our community, our children, our future,” sounds true to the immediate needs of the Navajo people to prepare for the sustainable future. However, the bill will not be passed without backlash. If the bill passes, the Nation will become entangled in legal pursuits from neighboring tribes, environmental groups and potentially the federal government.

“We will use every tool to prevent this from happening. If laws are broken we will sue, we will advocate and campaign. We will support the Navajo people who are against it,” Dahl said.

Advocacy groups, such as the family based Save the Confluence and Grand Canyon Trust – a conservation group dedicated to the preservation of the Canyon, will continue to block the project to preserve the pristine landscape and cultural significance of the Confluence.

“[The project] would be a desecration of a place that was not only sacred to the Navajo but also people of the world. To make it easier and more convenient would really destroy the reason why it is so special and so sacred to so many people,” Roger Clark, program director at Grand Canyon Trust, said.

The bill is intended to reach the Navajo Council in late January 2017.

Comments are Closed