Shark Valley visit busts Everglades myths

SHARK VALLEY, Fla. — As a Floridian, you will exhaust some state tourist destinations by the time you graduate high school. Thanks to all the field trips and family outings, I have visited most of the attractions found between the Florida Keys and Orlando.

While I now know Mickey on a first-name basis, something was always missing from my experiences. Something that was nearby, yet seemed so far away, so elusive: it was the Florida Everglades.

| Click to see a slideshow of the Shark Valley tram tour photographed and narrated by writer Ashley Calloway. |

Cue me driving along U.S. 41 west towards Everglades National Park’s north entrance. I am slathered in mosquito repellent and have packed a PB&J sandwich, should I get hungry out there in the wilderness. I’m ready.

I know what to expect: murky swamp water, dangerous animals and, of course, large swarms of blood-thirsty mosquitoes zipping through the stifling air. In an effort to get an in-depth look at this land, I have opted to take the two-hour guided tram tour offered at the Shark Valley Visitor Center.

Our tour guide today is a spirited woman named Diane Salino. She has a tan and an accent I can’t quite place. As I load into the tram with the 16 other passengers, mostly couples, Diane warns us to stay seated when the tram is moving, lest she has to slam on the brakes or swerve out of the way for animal.

“Wildlife is a wild guess,” she tells us.

After we get settled into our seats and Diane is in hers, she picks up the microphone that projects her voice through the tram’s speakers.

| A hump-back alligator that the park employees refer to as “Quasimodo,” after the character in the Hunchback of Notre-Dame. They are not sure what caused him to have a hump. He is very territorial, so the only other alligators you will see near him will be females, or his current “Esmeralda” (Photo by Ashley Calloway). |  |

“Who’s ready for some swamp living?” she asks.

“I am, I am!” I think to myself.

The passengers answer back coolly, but she stops them mid-response. The Everglades is not a swamp, she explains.

“We have nothing to blame but the media,” Diane says about this false assumption. What the Everglades is, in fact, is a “grassy river.” And so began my education of the Florida Everglades.

As we speed off, southward along the Shark Valley Loop Road, I realize that Diane is absolutely right. As far as my eyes can see, there is grass and trees and water—and not the murky water of my imagination. It is radiant water, some so shallow and clear that I can see to the bottom. The air is crisp and the movement of the tram creates a gentle breeze against my face. There is not an angry swarm of mosquitoes in sight.

|

A great blue heron that captured everyone’s attention, as it was only a few feet away from the tram. If you look closer, you can see an alligator swimming in the water behind it. Below, a view of pond near the base of the Observation Tower (Photos by Ashley Calloway). |

“Look at this as a river,” Diane says later, “and you can see it’s not that dark, dreary, dramatic place.”

On its website, Everglades National Park and Shark Valley promised visitors a chance to “see wildlife and learn about the Freshwater ecosystem.” No false advertising there; within seconds of us heading down the road, the tram comes to a stop. Diane has spotted an alligator in a small pond, or, as she puts it, “an eight-ball in the side pocket.”

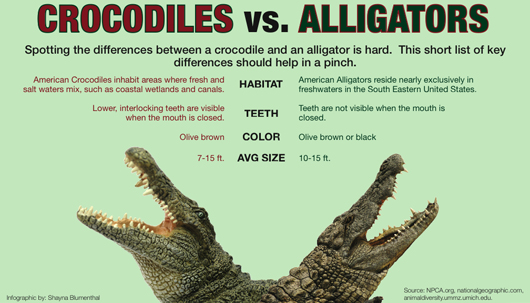

She refers to the alligator as an eight-ball because, contrary to popular belief, alligators are not green, but black. As I look closer at the head and eyes poking out of the water, I realize that Diane is absolutely right. Again. Another myth of the Everglades debunked.

After the passengers snap an excess of pictures of the alligator, the tram speeds off again along the road, but we don’t keep driving for too long. Intent on making sure we take in every sight possible, Diane hits the brakes every time she sees another animal.

There’s more alligators, great egrets, blue herons, great blue herons, tri-colored herons, kingfishers, ibis, wood storks, anhinga … all against the serene backdrop of tranquil waters, swaying grass and bunches of leafy trees.

“I wanted to give you all a chance to get your first impression of the Everglades,” Diane says as we take everything in at another stop.

“I wanted to give you all a chance to get your first impression of the Everglades,” Diane says as we take everything in at another stop.

She offers up details about the animals we observe—how a healthy alligator can grow a foot a year, how the blue herring’s color comes in completely when it fully matures.

She explains that the Everglades National Park is the third-largest national park in size in the contiguous United States and the best in terms of biological diversity.

A passenger compared it to New York, the melting pot of cultures. And, fittingly, it turns out that’s where Diane’s accent originated.

The drive down the road is also dotted with facts about the vegetation and more popular myths are shot down. Take the vultures, which Diane compares to New York’s sanitation workers. Contrary to what we see in Disney movies, vultures are not birds of prey.

“Vultures are not bad things,” Diane says, as they swoop beside our tram. She explains that they help keep the park clean by consuming the dead animals.

We then see another bird that demands a halt of the tram and the attention of everyone on board. Another great blue herring, but this one is only a few feet away from the road. The tram is in awe of the majestic bird.

“That is magnificent,” gasps the woman in front of me. “Look at that plume on the neck there—Oh, God.”

Around this point I realize that we are all as excited and fascinated by this tour as kids at a theme park. And how could we not be? Save the paved loop, we are surrounded on all sides by this grassy, animated land that springs up right where the edge of the road stops.

The park enthralls us even more when we take the 15-minute stop at the Observation Tower, which gives an 18-mile, 360 degree view of “the western edge of ‘The River of Grass.’”

From here we can spot a flock of birds landing on the treetops in front of us, or the rippling ponds sprinkled with lily pads and shoots of grass. We see part the loop we just traveled, weaving its way through the beige, brown and green rainbow of the valley.

| At right, the alligator that was lounging near the trail. After the tour, many of the passengers walked back to snap a picture of him. We all felt a bit braver after our tour guide, Diane, explained that alligators are not inherently violent animals. Below, a flock of birds flying across the sunset, after the tram tour had come to an end (Photos by Ashley Calloway). |  |

As we gaze from the top of the 45-foot tower, Diane imparts more knowledge on us. She explains that the Everglades is not just a national park; the park is only a region of the actual Florida Everglades. The Everglades was once eight billion acres, but now, thanks to development, there are only 2.5 billion acres left.

“Very sad story,” Diane says, “All in the name of so-called progress.”

The Observation Tower itself was initially part of an oil well, but the oil found there was loaded with impurities that couldn’t be removed with older technology. The disappointed oil company handed the well to the park.

We make our way down the oil-well-turned-tower and to the tram for the last seven miles back to the park’s visitor center. Trying to make time, Diane stops less frequently, but the information keeps flowing. She talks more about the wildlife and vegetation of the park as well as the history of the Miccosukee Indian tribe.

And, of course, she makes it a point to challenge things we thought we knew about the Everglades and its inhabitants. On the last stretch of the loop, we pass a few more alligators, including a six-footer lounging just inches away from the trail.

This is the same trail that bicyclers have to use to make their way through Shark Valley. This can’t be safe. The alligator is a bit too close to the tram, now that I think about it.

“Gators are very passive,” Diane says, noting our concern, “Unless you feed them. Gators don’t know the difference between a hand and a handout.”

She goes on to tell us the park will soon be 62 years old, and park officials have never had an account of a human being attacked by an alligator. On the outskirts, where some people feed the alligators, things can become dangerous.

As the tram rolls to a stop back at the visitor center, my mind is still swimming with everything I took in today.

As the tram rolls to a stop back at the visitor center, my mind is still swimming with everything I took in today.

The Everglades is not the gloomy, hazardous swampland I imagined it to be. It’s bright and lush and teeming with life, as well as South Florida history. All I needed to see that was a real look at the park—and, of course, an amazing tour guide.

Armed with the consolation that we were indeed not going to be attacked by the alligator, a few of us crept back over to where the reptile was lolling by the trail.

We whipped out our cameras and tip-toed closer, much closer than we would have had Diane not dispelled the whole inherently-dangerous-alligator myth.

One woman next to me was still adjusting to the facts, hesitantly moving closer as her partner coaxed her forward. We were both only a few feet away from this mystifying creature, whose image had changed for us after the tour.

“Who knew?” she says to me, shaking her head in disbelief. “It’s like a secret!”

A well-kept secret, indeed. I feel like I had been let in on a lot of information. It was a safari, history lesson and a Discovery Channel special, all compacted into a two-hour tour. And the Everglades, this backyard land that was once such a mystery to me, became a lot less elusive.

If You Go…

Address: 36000 SW 8th St., Miami, FL 33194.

Shark Valley Visitor Center of Everglades National Park is located on U.S. Highway 41 (Tamiami Trail or SW 8th Street). From the Miami area to the east, it is about 25 miles west of the Florida Turnpike, exit 25A (from the north) and exit 25 (from the south).

From the Naples area on the west coast, take U.S. 41 (Tamiami Trail) approximately 70 miles east to Shark Valley.

Telephone: 305-221-8776.

Open every day of the year. Tram tours depart every hour from 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. from late December through April; depart four times a day from 9:30 a.m. – 3 p.m. from May to late December.

Tour Rates: $16.25 for adults; $15.25 for seniors (62+); $10 for children (3-12).

$10 entrance fee for vehicles.

For more information, visit http://www.sharkvalleytramtours.com

Information graphic designed and prepared by Shayna Blumenthal.

Comments are Closed