Field trip gives students look at marine life

HOMESTEAD, Fla.— The clear blue water of the Atlantic Ocean was a welcoming sight, especially after having spent close to an hour on a school bus with nearly 40 high school students as we all made our way to Biscayne National Park.

It was the Wednesday before Thanksgiving and I had volunteered to chaperone a field trip with marine science students from Miami Sunset Senior High, accompanying my 16-year-old sister and her classmates. As the students went through a short orientation, I asked what my responsibility as chaperone was.

|

Marine science students from Miami Sunset Senior High attend a seagrass experience field trip (Photo by Megan Ondrizek). |

“Oh, you’re a chaperone? Just make sure the kids don’t do anything stupid,” I was told by one of the three Biscayne National Park naturalists assigned to our group. Easy enough.

Soon after orientation, the class was split into three groups of about 12 to 15 students, each led by a naturalist and chaperone. I followed my group through the sand dunes and on to the beach, each of us carrying a neon yellow life vest, specimen buckets and nets in hand.

Transparent blue blobs lined the shore—Portuguese man-o-war, we were warned; if you see them floating near you in the water, keep a safe distance and you won’t be stung.

As I walked down the beach with my net thrown over my shoulder, I couldn’t help but think back to the times I had participated in this very same program: first as a fifth grader at Joe Hall Elementary School and again with my marine biology class as a senior at G. Holmes Braddock Senior High.

Both of those field trips were quintessential educational experiences—and I was excited to see if I remembered anything I had learned nearly four years ago. A five-minute trek down the beach brought us to the location our naturalist, Shana, had scouted. Low tide spanned for at least one mile off shore and the 10 a.m. sun was positioned perfectly. It was a great day to collect organisms that live in the seagrass habitat.

I carefully made my way into the water at my own pace, cursing the cold (under my breath of course — I was supposed to be an example to the students, after all) as my sneaker-protected feet engaged in the “Stingray Shuffle” so as to avoid an unfriendly encounter with the poisonous barbed marine animal.

Once all of the students in my group were situated and seemingly comfortable with the water temperature, we divided once more into groups of two and dredged through the seagrass beds less than 50 yards off shore.

| Seagrass habitats offer an ideal nursery environment for fish, sponges and other marine organisms (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

Shana waded close by with specimen buckets and fish net in hand, ready to hold whatever the students managed to catch in their nets. I thought she was more than qualified to instruct a high school group, since she had earned her bachelor’s degree in marine science from the University of Miami nearly four years ago.

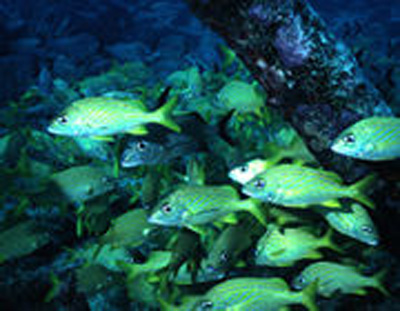

Sounds of delight came from students as their nets yielded interesting catches: pike fish, filefish, boxfish, different species of sponges and even a baby seahorse. The nets were too small to handle the live conch that we also found, but it was still considered a catch of the day—more so after the students were each given the chance to examine the animal, albeit while slightly disgusted.

After a little more than an hour, the final specimens were placed in the buckets and each group made its way back to shore, sitting on the beach as each naturalist described what they had gathered in a sort of crash-course to marine science.

I was content with the lesson, especially since I could recall some of the information I had learned as a marine science student. The students were active in the lesson as well, offering information they had learned in the classroom when it was asked for. Once the lesson was over, every organism was returned to the water, unharmed and left to mature in the nursery habitat the seagrass provides.

The field trip opportunity allowed students to apply what they had learned in the classroom, something that is necessary for complete understanding of the subject.

|

Grunt fish hatch in seagrass nursery habitats and use the nutrients to mature before moving to coral reefs (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

Andrew Anderson, a marine science teacher at Miami Sunset Senior High School and the organizer of the field trip, is a strong advocate of the educational programs the center offers.

“If a student is going to take marine science, they should get as many chances as possible to see what’s out there,” Anderson said. “I want them to take a perspective of marine science with them.”

And, following the seagrass dredging experience, it is safe to assume that the students will do just that. Or at least have a great story to tell friends.

If You Go With a Class…

- For more information on planning a field trip to Biscayne National Park, contact Education Program Coordinator Maria Beotegui at 305-230-1144, ext. 3037.

- The Education Center at Biscayne National Park offers three different programs: day, overnight or classroom. Day programs include a ranger-led wildlife inventory and a teacher-led discovery pack.

- Information for teachers may also be found online at http://www.nps.gov/bisc/forteachers.

Comments are Closed