Wildlife management critical for success

A majestic symbol of the great American frontier has become the subject of one of the most pervasive issues plaguing western national parks today.

Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Badlands National Park in South Dakota have enacted plans to contain two major issues surrounding bison, population size and the spreading of brucellosis, a disease that inflicts mammals and could cause them to abort fetuses.

|

Bison roam open space at Yellowstone National Park (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign, National Park Service). |

“The bison are for public enjoyment and to restore the natural ecosystem as best they can. They are in a contained area, it’s not like years ago when they could roam free all over, and we try to manage that,” said Julie Johndreau, education specialist at Badlands National Park.

At Yellowstone, the nomadic herds of bison graze over the grounds of the park until winter when the ground is covered with snow and bison cannot locate food. This forces them to leave the park for lower altitudes in the adjacent Montana where grazing areas are still available. Cattle also graze on these areas at times and could become infected with brucellosis if they interact with an infected bison.

Brucellosis can be transferred through casual contact with an infected animal or from contact with birthing fluids from an aborted fetus that came from an infected animal. Not only are bison and cattle affected by the disease, but also elk, moose and other wildlife commonly found in national parks.

This becomes a problem for livestock companies in Montana that rely on continuously growing cattle populations for goods and revenue.

To combat the issue, five agencies agreed upon the Interagency Bison Management Plan in December 2000. The National Park Service, the U. S. Forest Service, USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Montana Department of Livestock, and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks drafted the plan.

| A bison braves the brutal winter weather (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |  |

The official purpose of the IBMP is to “maintain a wild, free-ranging population of bison and address the risk of brucellosis transmission” to livestock. To fulfill its purpose, the IBMP dictates how and where bison are allowed to move and how the threat of brucellosis will be controlled.

“The Interagency Bison Management Plan is based on the adaptive management strategy that allows the agencies to gain experience and knowledge before proceeding to subsequent management steps,” said Teresa K. Howes, public affairs specialist with the USDA APHIS. “Based upon research and/or adaptive management findings, elements of the plan may be modified. This plan addresses spatial and temporal separation and risk management to minimize transmission between cattle and bison.”

The IBMP says that in the winter months, if bison move outside of park boundaries, they will first be hazed back into designated management zones. If the hazing is unsuccessful, the bison still outside of the park will be captured and tested for brucellosis.

If bison test positive or do not go into the capture facility, they will be killed. If bison test negative, they can remain in a designated management zone, as long as there are 100 or less bison there at the time.

“The bison removals at this time are for brucellosis risk management, but it acts as a defacto method of population control,” said Rick Wallen, Yellowstone wildlife biologist. “When we have high populations during intense winters, more bison leave the park and our management methods keep the bison population inside the parks.”

During winter 2006-07, there weren’t any bison captured or tested.

Bison did not need to leave the park in search of forage because of the mild weather and minimal snowfall.

|

| Graphic courtesy of the National Park Service. |

Some animals did move towards the park boundaries, but were hazed back by park officials.

“This year we were able to manage them through creative hazing. We monitored the bison and, when we detected something, we mobilized with our ranger core and set up a human barricade where we moved back and forth moving them in the right direction.

“We then followed them and moved them to a location near management area, there’s a line of tolerance if you will. The key is daily monitoring. This year most of the activity was really near the line of tolerance. We had to mobilize eight or 10 different times to move animals back to that area,” said Wallen.

While Yellowstone’s management plan focuses on the threat of brucellosis, Badlands National Park implemented a plan that is concerned with population control.

“Our goal is to reduce the population the park because we have such a large population. If we didn’t manage them, they would eat themselves,” said Johndreau.

Their management plan integrates provisions set by the Intertribal Bison Cooperative.

|

A staff member rides a snowmobile near a bison herd as part of the management of the animals at Yellowstone National Park (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |

This agreement allows for Indian tribes in neighboring areas to receive bison that are removed from the park due to overpopulation.

“Bison that are sent to Indian tribes are used to start populations of bison in tribal areas.

They are either starter animals to get a herd going or they are used to augment an already established herd,” said Johndreau.

When bison move north of the boundary of the park, they are corralled and then tested for brucellosis, Johnes infection and they are genetically tested so the park can best determine how to handle each specific bison and herd.

“This past fall we processed 657 bison. We have a very genetically healthy and diverse heard, which is a really great thing,” said Johndreau.

However, the execution of plans such as these was followed with harsh criticism from animal rights groups and government officials alike.

“I think the plan is failing the bison. It isn’t sustainable for bison and it’s a very poor way to manage wildlife,” said Amy McNamara, national parks program director for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. “For every other animal, there isn’t this artificial boundary that bison face. Bison are treated quite differently. They migrate as other animals do and they look for other habitats as other animals do, but they have this poor management plan.”

| Riders on horses supervise a herd of bison at Yellowstone National Park (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |  |

Many groups, including the National Park Service, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Defenders of Wildlife, and the governor of Montana have delivered their opinions and weighed in on the controversial issues.

“Bison management at Yellowstone is a very contentious issue. Many agencies are involved, including three federal agencies and two Montana state agencies. Trying to make decisions based on ideas is very difficult. A lot of times outside groups will be recalcitrant and spend a lot of time on personal values and politics when they’re not sure of the actual issues. An issue of this kind of controversy takes a lot of time for a decision put out,” said Wallen.

Because Montana has had a brucellosis-free status since the IBMP was implemented and there has never been a recorded case of a transmission of brucellosis in the wild, some activists believe the management plan should be modified to prevent violent hazing methods and the slaughter of bison.

This issue became extremely heated when more than 900 bison were captured and killed during the winter of 2005-06, the most bison killed since 1997.

“I think it’s important for Montana to maintain its brucellosis-free status, so we have to find a mechanism for managing bison population while preventing their co-mingling with cattle,” said McNamara. “We advocate a plan that would make it so when bison are outside of the park; they are separated from cattle in both space and time, which would prevent any co-mingling”

|

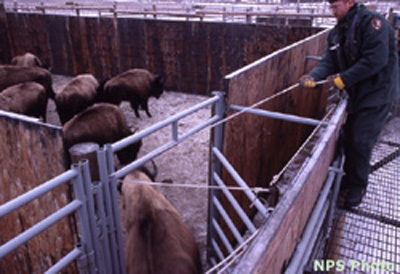

Captured bison are kept in pen to await tests for diseases (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |

The Greater Yellowstone Coalition, among other groups, advocates an organized and regulated hunting of bison in the winter months. There are lands outside of the park where the bison can be hunted and where they wouldn’t integrate with cattle. A hunt would maintain a stable population as well as encourage tourism of hunters, provide bison meat to the local food industry and increase revenue for businesses that cater to hunters.

Additionally, activists are calling for more space for bison to find food in the winter and a more effective vaccination program. According to its website, the Defenders of Wildlife “recommend mandatory vaccination of cattle within and immediately adjacent to the special management area.” However, it will take years before such a stringent plan becomes reality.

Currently, there is a limited vaccination program in place. If animals test negative for the disease after being captured and are allowed back in the park, young animals that were captured and not pregnant would be vaccinated.

“Planners envisioned a much broader and expanded plan of vaccination, expanding the plan to bison on all ranges of the park,” said Wallen. “We haven’t made any decisions yet. The park is currently going through a review session. In 2008 most likely there will be a public review session and after that a decision can be made.”

There was an oversight hearing on Yellowstone National Park bison held by the U.S. House of Representatives on March 20, 2007. Wildlife experts, government officials and parks officials each testified with their favored alternatives for finding a solution to the bison management issue.

| A park ranger works with bison in their pens (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |  |

U.S. Rep. Nick Rahall (D-WV), chairman of the Committee on Natural Resources, called for ending the slaughter of bison as a means of containing a disease.

“Slaughter is not management,” Rahall said in his opening statement at the hearing. “It is an approach from a bygone era and has no place in a time of rapid scientific and economic progress. We are capable of more ingenuity and more compassion if we are willing to try.”

The IBMP is currently being reviewed. Everyone connected to the controversy surrounding bison management is eagerly awaiting an outcome that will lead to a change where all parties involved can feel some satisfaction and most importantly, where slaughtering bison will be a last resort rather than the best option.

|

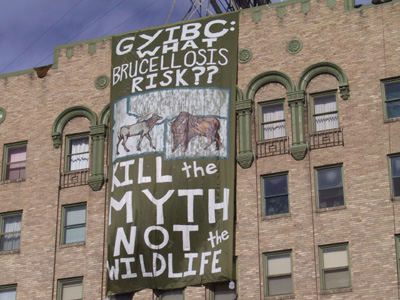

Activists express their views about bison control in the western U.S. (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo Field Campaign). |

Comments are Closed