Underused parks create awareness, access

In the summer, Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park is at once warm and filled with swarms of mosquitoes in its valleys and cold and filled with snow in its utmost elevations.

If such diversity is contained within one park, imagine the variety present in a park system that spans the entire United States and its territories.

Dry Tortugas National Park, 5,000 miles southeast of Wrangell-St. Elias, lies off South Florida’s coast. Here, the view isn’t of mountains and glaciers, but of a never-ending ocean surrounding the park’s centerpiece, Fort Jefferson.

| At right, loblolly pines soar over Congaree National Park (Photo by Theresa Thom, National Park Service). Next, Mount St. Elias in Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park (Photo by Valentin Sommer, National Park Service). Last, Fort Jefferson in Dry Tortugas National Park (Photo courtesy of National Park Service). |  |

Seven hundred miles from Dry Tortugas, in South Carolina, is Congaree National Park where trees reaching 167 feet tall watch over its otter- and heron-filled floodplains.

Though so different, these parks share the same goal. Each represents a region of the United States left wild.

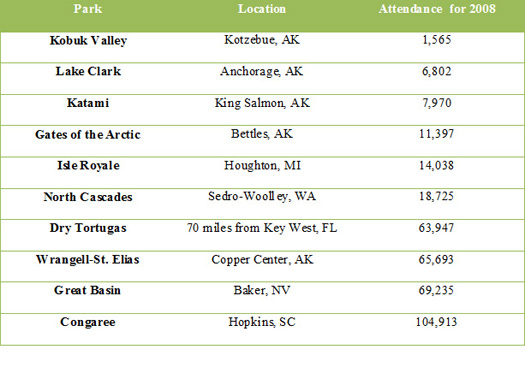

They also share the same struggle. Despite each park’s status as a natural treasure, each is plucked from the list of national parks with the fewest visitors.

That list is filled primarily with remote parks. Wrangell-St. Elias and Dry Tortugas are not exceptions. The latter is surrounded by ocean, the former by Alaska.

For park experts such as Linda Roehrig, Special Park Uses Program manager at Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks, the isolation is part of the allure.

Roehrig remembers her first visit to Dry Tortugas, before she was in its employ.

“I was impressed… by the fact that it is so far from civilization,” she said.

The park, which is a series of seven small islands about 70 miles west of Key West, Fla., must be reached by private boat, commercial ferry, or seaplane.

The thrill of the undiscovered still stirs the spirit of adventure inside Mark Keogh, the Public Information Officer and Concessions Management Specialist at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park.

“We bring people to climb peaks here that have never been climbed before. Many have yet to be named,” he said.

Keogh doesn’t want to have the park all to himself, though, and neither does Roehrig. They want others to enjoy these places they work so hard to preserve.

Keogh doesn’t want to have the park all to himself, though, and neither does Roehrig. They want others to enjoy these places they work so hard to preserve.

Each of these parks hosts around 60,000 guests a year.

Visitors to Dry Tortugas spend at least $145 roundtrip and two hours each way to be transported from Key West to Garden Key, the island on which Fort Jefferson sits with its 360 degree gaze set on the rest of the park.

Wrangell-St. Elias is accessible by highway, but it’s in a state with population density of about one person per square mile. Roads into the park are few and the park is vast. In fact, it is the largest park in our system, the size of nine states. There, glaciers even draw state comparisons. For example, Malaspina Glacier is Rhode Island-sized.

Further inhibiting park attendance is the severity of Alaska’s winters. The average high, across the entire year, is 38.6 degrees Fahrenheit. The average low is 15, though it is not uncommon in the winter for temperatures to dip as low as negative 50 degrees.

According to Keogh, it’s in the summer when everything comes alive.

For Congaree, in relatively temperate South Carolina, weather does not deter many visitors. Nor is isolation a problem. Half an hour from the park is its home state’s bustling capital at Columbia.

As a national park, however, Congaree is still in its infancy. In 2003, Congaree Swamp National Monument became Congaree National Park. Word is getting around about this, the 58th and newest national park, and attendance is rapidly increasing. Since Congaree became a national park, attendance has nearly doubled, but to eventually attract the crowds it deserves, the park has to take part in some self-promotion.

But the national parks do little advertising.

Superintendent of Congaree National Park Tracy Swartout explained how parks without advertising budgets attract visitors.

“A lot of our visitors find us in guidebooks, which we don’t have to pay for. When there’s a local guidebook that asks for us to pay for an ad I say, ‘Would you really publish a book about South Carolina without including its only national park?’” she said.

Park attendance numbers for Congaree began their doubling after the park was universally featured in national park guidebooks, such as the newest edition of National Geographic’s Guide to the National Parks of the United States.

Another means of promotion for the parks is the website. Roehrig stressed the importance of Dry Tortugas’ official park website in drawing crowds to its shores.

Keogh echoed Roehrig, adding that proposed podcasts will enable those who cannot make it to Wrangell-St. Elias National Park to still feel a part. The fruit of effective park marketing isn’t a giant line, but increased awareness of the park and its resources.

Facebook and Twitter will one day provide a supplement to park websites, according to Swartout who mentioned that park policy recently shifted to allow use of these social networking media by the parks to promote themselves.

Facebook and Twitter will one day provide a supplement to park websites, according to Swartout who mentioned that park policy recently shifted to allow use of these social networking media by the parks to promote themselves.

Currently, private entities such as The National Parks Foundation maintain such sites for the national parks.

Parks also host special events inside and outside their bounds to draw repeat visitors and first timers, respectively.

For example, Congaree, with the help of partnership funding, set up an exhibit at this year’s South Carolina State Fair, complete with a replica boardwalk, tree samples and taxidermy specimens, to reach the 200,000 visitors at the fair.

“Some Columbians had no idea that the only national park in South Carolina with the tallest trees east of the Mississippi was right in their backyard,” said a disbelieving Swartout with an air of optimism.

South Carolinians that were previously unaware of the park represent a formerly untapped market of future repeat visitors.

Some parks have private businesses doing some of their promotion in the form of tour groups. The ferries of Dry Tortugas and the aircraft of Wrangell-St. Elias promote themselves and, in doing so, promote the parks.

Another means of advertising is absolutely free: word of mouth.

Visitors to Wrangell-St. Elias tell of the “magic” there – a word Mark Keogh used often in describing the park’s jagged and uncharted landscape.

Visitors to Dry Tortugas tell of the ocean breezes felt while looking upon the beauty of the park.

And visitors to Congaree tell of its serenity – a tree-filled enclave amid suburbia.

The National Park Service challenges us to “Experience [Our] America.” To fully take up this task, one must not forget these, the hidden gems of our park system. They contribute uniquely to our landscape as remnants of what was, scattered widely among what is our America.

Underused National Park Service units

Comments are Closed