Parks minimize effects of natural disasters

The serenity of a natural park is unquestionable.

But this serenity at any point can be attacked. Imagine this peaceful place turned into a place where nerves are frayed. Imagine the blue skies covered in a thick blanket of smoke and the trees showered in ash.

In Georgia that was exactly the problem.

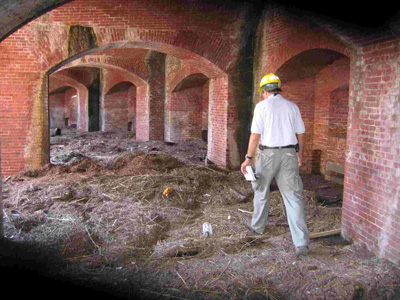

|

Debris covered the interior of Fort Massa- chusetts at Gulf Islands National Seashore, Mississippi District, after Hurricane Katrina (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

On April 16, a wildfire fire ignited in southeast Georgia, a fire that has consumed nearly 100 square miles. While the fires did not threaten any national parks in this instance, the shifting winds and drought-parched state forests only fed its hunger. Firefighters scraped for hours to contain the fire and protect the homes that it threatens.

Wildfires and natural disasters of this type always threaten the nirvana of our parks. It is a particularly severe problem in the west, but the problem affects almost all of our national parks.

Almost e veryday, policies and plans dealing with national disasters such as wildfires and floods are rewritten, rethought and reapplied so that the present and future damage might be minimized.

“Wildfires are completely impossible to prevent,” said Firewise Communities support manager at the National Fire Protection Association Michele Steinberg.

It is a naturally occurring phenomenon in which most U.S. ecosystems are adapted to it. However, wildfires are getting worse and the way they are dealt with has also changed. .

“Today’s fires can become unusually fierce because Smoky the Bear went overboard,” according to a Jonathan Tourtellot National Geographic article, referring to fire fighters from the National Park Service (NPS) and other federal government agencies.

|

Grandview, on Grand Canyon’s South Rim. Dense thickets and weakened old trees, a condition attributed to competitive stress resulting from fire suppression (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

In the past, fires were completely suppressed, allowing a build up of too much fuel like dead wood and underbrush; making small grass fires into disastrous forest fires.

“The introduction of this evasive grass causes more combustion,” said Holly Bundock, NPS assistant regional director of the Pacific West region.

Now the national parks follow a different policy.

According to Tina Boehle, a NPS fire communications and education specialist, once a fire has started, the fire is investigated for its origin. If it is found to be a human start, then the fire is completely suppressed.

However, if the fire is natural, such as a lightening strike, then it depends on the area in which the fire is located. But more than likely it will be allowed to burn.

This decision is made after deliberation at the park level, and might be brought under incident management.

“If the fire occurred in natural conditions and it is non-threatening, as we are not like forestry and worried about timber for sale, we would let it burn,” according to Biscayne National Park’s supervisor park ranger Tom Routledge.

|

Rainbow Plateau, south of Swamp Ridge on Grand Canyon’s North Rim, taken by Pete Fule of Northern Arizona Uni- versity. (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

Routledge has been sent around the U.S. to fight fires.

Some parks even decide to start a small fire in a secluded area, called a control burn, to regenerate new growth according to Linda Friar, public information officer at Everglades and Dry Tortugas parks.

Once a decision has been made, the park fire fighting team is called in – most parks have their own teams. A job once placed on rangers is now being done by fire specialists in the Everglades, stated Routledge.

A typical fire fighting squad consists of 20 fire fighters: a crew boss, an assistant boss, three squad bosses and 15 firefighters. And these squads are called into around the country if need be. National parks work together when fires get out of control and they lend each other support.

“Wildfire season never ends, only rotates,” said Boehle.

A year-round threat rotating around the United States and a year-long struggle in Southern California, wildfires are never forgotten.

El Nino, heat wave and drought are major contributors to wildfires. And in southern California, the Santa Ana winds – non stop winds that are very dry – only add to the likelihood of a wildfire starting or becoming harsher, said Boehle.

And to help conditions worsen, Bundock explained that the dry season is becoming longer. It starts earlier and ends later.

|

Park prescribed fire hand-crews “stringing fire” in a North Rim burn unit, in cautious incremental strips, to keep burn severity to prescribed levels (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

Even though wildfire is a major threat to any national park, national parks must also be on guard and prepared for any natural disasters.

All U.S. regions have a natural disaster that may threaten them. California has earthquakes, the Midwest have tornados, and let us not forget Florida and the Gulf of Mexico region’s hurricane threats.

Each a different natural disaster, however, in the end all treated the same from the eyes of the national parks.

According to Bundock, a special events team would be assembled when and if a disaster were to happen. Each member would have specific rules/jobs such as human safety, logistics and search and rescue.

And this special events team is created for a variety of reasons ranging from floods and earthquakes to even a special event such as the president coming to visit.

In the Florida parks, officials at Biscayne, Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks tend to worry most between the months of June and November when hurricane season arrives.

In a case of a hurricane, rangers are trained in an NPS system called the Incident Command System (ICS).

|

Swamp Ridge, on Grand Canyon’s North Rim. The unnaturally dense thickets of white fir invade a once dominant old ponderosa pine forest (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“ICS is for all types of incidents and rangers have been detailed to emergencies inside and outside park areas, as well as internationally. There are currently two Type I national ICS Teams available for deployment and five regional Type II ICS Teams,” according to the NPS mission overview document.

This ICS developed out of fire fighting and has been used in all instances when a national park has been hit by an overwhelming situation, like a hurricane or earthquake.

However the ICS is not the only thing parks rely on.

A park might choose to development a plan, a guideline for when the situation arises, a blueprint to follow. And this is exactly what the Everglades and the Dry Tortugas have.

In a detailed 111-page plan, last updated in 2006, the park outlines what needs to be done in the event of a hurricane striking.

This plan is always being updated and it was after the devastation of Hurricane Andrew that the plan received a detailed make over.

“This plan has also served as an example to many other areas of the National Park Service and U.S. Department of Interior, and in that manner has experienced considerable other testing and application,” stated in the introduction of the Everglades and National Tortugas hurricane policy.

|

Fort Pickens Road and J. Earle Bowden Way remain closed because of beach erosion in Florida (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

And its success was proven in 1999 when Hurricane Irene changed its track and made landfall at Cape Sable and the Everglades National Park..

The plan is based on the ICS and explains that hurricane preparation is a year-round job. Furthermore it outlines distinct periods: general hurricane season, preliminary hurricane preparation (72 to 48 hours before), advanced preparation (48 to 24 hours), final preparation (24 hours), post hurricane recovery and hurricane breakdown (when a storm does not hit).

And each branch is given its own checklist so that nothing is left unturned.

The meetings and preparation begin as early as April. And when the national park finds itself in the prospective path of hurricane, even if still uncertain, the plan is kicked into overdrive.

“For more severe incidents an instant command team is created,” said Everglades park spokesperson Linda Friar.

Even after much preparation, the national parks have a lot of work to do after the storm hits. A year later and some parks are still left with scars from the winds and rain.

“Keys were reshaped, new channels were opened, shallow water seagrass was removed from areas and large areas of the keys were denuded of terrestrial vegetation,” taken from a briefing statement from Friar explaining some of the damage sustained by the parks after the 2005 season.

Although emergency funding is available and federal organisations are sent to help, money is an issue.

“We are still in recovery and long term planning is needed,” said Friar.

|

Grand View on Grand Canyon’s South Rim in 1909 (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“Quarters for six NPS employees still have not been replaced nor has the NPS vehicle fleet that was damaged by Katrina. Also still awaiting replacement are the maintenance facilities which were damaged beyond repair,” according to a briefing statement written by Friar on Sept. 12, 2006.

Almost a year later and into a new hurricane season, the damages were still not fully repaired.

Regional and national NPS teams are sent to aid in the recovery. Like the special even teams that Bundock explained. Those teams were sent to Louisiana in the recovery effort after Hurricane Katrina, and here to Florida after Hurricane Andrew.

The policies for both wildfires and natural disasters are quite simple: Preparation is the key and each new incident brings about new ideas to upgrade this plan or policy.

Comments are Closed