African Burial Ground recalls slavery era

NEW YORK, N.Y. — I have lived in New York my whole life, just blocks from Times Square, the heart of the city where fast-paced New Yorkers obliviously type away on their cell phones, seemingly unaware of their surroundings, and overlooking Central Park, the only park most people equate with New York City.

I have lived here for 21 years, but it was not until I visited the African Burial Ground National Monument here did I become aware of the real history that laid the foundation for this city I call home.

| Click on the video to see a slide show about the African Burial Ground National Monument photographed by writer Lindsay Noris. |

It was not until I made the trek all the way downtown from my Upper West Side apartment did I learn of the fragments of history that my high school U.S. history textbook failed to mention. These are the parts that most people like myself just do not learn in school.

Located in downtown Manhattan, the African Burial Ground was created in 1991, during the beginning stages of an excavation for a new federal building, during which workers came across the skeletal remains of 419 enslaved and freed blacks originating from various parts of Africa. The grounds were recognized on March 4, 1993, as New York City’s first underground landmark and, on April 14, 2007, it soon became a national monument.

| At right, a cosmogram at the center of the monument, which stands for the crossroads of birth, life, death, and rebirth in Congo cosmology. Next, below, a park ranger speaks to visitors outside the entrance of the Visitor Center in the Ted Weiss Federal Building. Next, the entrance to the African Burial Ground National Monument Visitor Center. Next, the African Burial Ground National Monument, designed by Rodney Leon, and the mounds of grass where the remains of free and enslaved Africans were reburied after excavation. Next, a West African Akan symbol called a Sankofa is inscribed on the side of the monument. It represents the idea of returning to our roots to learn from the past in order to improve the future. Last, the monument is oriented in the same direction as those buried underneath it, towards the rising sun (Photos by Lindsay Noris). |  |

On the Friday after Thanksgiving, my curiosity got the best of me and I found my mother, Barbara Noris, and myself taking the 20-minute cab ride downtown to explore the area that marked a small portion of the 6.6 acre sacred remains of an African burial site from the 17th century.

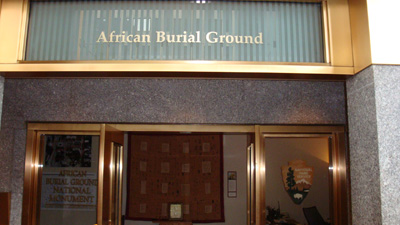

As I entered the massive government building at 290 Broadway, I was quickly guided through airport style security screening, and directed to the African Burial Ground visitor center discretely placed in the far corner of the building.

The center, comprised of one small room and a resource library, was an insignificant area marked “African Burial Ground” that paled in comparison to the marble pillars and high ceilings that decorated the stunning and regal interior of the federal building.

The center, comprised of one small room and a resource library, was an insignificant area marked “African Burial Ground” that paled in comparison to the marble pillars and high ceilings that decorated the stunning and regal interior of the federal building.

In front of the entrance to the visitor center were rows of framed posters inscribed with the history of the monument and the missing pieces to New York City’s foundation.

Various commissioned pieces of artwork were scattered throughout the front hall, as well as replicas of the artifacts that had been found buried with the skeletal remains.

I was surprised to see only two additional visitors exploring the center, both of African descent.

“Did you know New York City had slaves?” I asked one of the women who had been studying the literature on the signs beside me.

“Of course,” Shelly Johnson, a vivacious student from a local college replied as she frantically scribbled down notes, “It’s part of our history. Some are recognized and others will remain forgotten.”

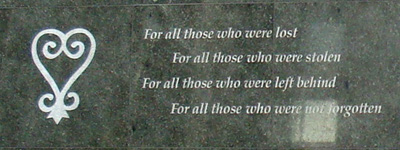

With the discovery of the burial grounds, history would be rewritten.

With the discovery of the burial grounds, history would be rewritten.

The grounds revealed that, despite what our U.S. history textbooks taught us, Northerners did in fact enslave Africans during the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and up to 20,000 people of African decent are believed to be buried under the ground in Lower Manhattan.

It also helped shed light on the rich culture and rituals of the African people.

The four of us were soon shuttled into a small room in the visitor center where a few artifacts hanged on the walls and where rows of seats were lined up in front of a single television set and a video player. This is where a brief 25-minute video recapping the history of the African slave trade and the discovery of the grounds is shown on a regular basis for visitors.

In addition to the video, there are also information sessions, exhibits, and various programs provided by the visitor center. Other programs, such as on and off-site educational programs are also offered for students and visitors, and reservations can be made for an off-site 90-minute walking tour about the presence of Africans in colonial New York, as well as ranger led tours of the national monument.

After watching the short video, I realized how important the discovery of the grounds were to those people of African decent currently living in New York City as well as to the history of the United States.

“The history behind this is fascinating, although I’m shocked and embarrassed that I was completely unaware of all of this while it was going on,” said Barbara Noris, “I lived here in ’91 and was oblivious to the press and uproar within the African American community because of the lack of respect they felt they were receiving at the time of the excavation.”

“The history behind this is fascinating, although I’m shocked and embarrassed that I was completely unaware of all of this while it was going on,” said Barbara Noris, “I lived here in ’91 and was oblivious to the press and uproar within the African American community because of the lack of respect they felt they were receiving at the time of the excavation.”

From a large window in the small visitor center, you can see the current standing monument, designed by Rodney Leon, signifying the past, present, and future.

It was built on top a small portion of the burial grounds, commemorating the bones of the deceased that lay six feet under, 40 percent of which were children.

After 10 years of studying the bones at Howard University, the remains were reburied with the ritualistic artifacts originally found in the graves. Mounds located in the grassy areas next to the monument represent these remains.

“We feel bad we robbed these graves in the first place, it’s horrible to disturb anyone’s graves, but on the other hand, we wouldn’t have known that New York was founded on slavery,” said Chris Forman, an enthusiastic park ranger, “We are here and proud to be here.”

“We feel bad we robbed these graves in the first place, it’s horrible to disturb anyone’s graves, but on the other hand, we wouldn’t have known that New York was founded on slavery,” said Chris Forman, an enthusiastic park ranger, “We are here and proud to be here.”

Forman noted that a new and improved permanent visitor center is expected to open in February 2010 with the hopes of attracting more visitors and a greater interest in and awareness of the national monument.

“It will be a lot bigger, a lot cooler, and will bring the site to life,” said Forman, “As long as there is the USA, we will be here telling this story, it’s unalterable, that will not change, we are here to stay.”

If You Go:

- Hours: Monday through Friday, 9 – 5 p.m., except federal holidays.

- Location: 290 Broadway on the first floor of the Ted Weiss Federal Building on the corner of Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way, also known as Elk Street. The website is http://www.nps.gov/afbg and the phone number is 212-637-2019.

- Admission: Visits are free, guided tours are available and reservations are encouraged.

- Facilities: A key is needed for bathrooms available in the Ted Weiss Federal Building and is handicap accessible. Dining facilities and gift shop are not available at the African Burial Ground National Monument.

- Getting There: Easily accessible by public transportation, parking is limited and difficult to find in New York City. The 4, 5, 6, R, W, J, M, and Z subways stop at Chambers Street and the 2,3 subways stop at Park Place. Buses include the M15, M22, B51, M1, and M6.

Comments are Closed