Vietnam Memorial honors war veterans

WASHINGTON, D.C.— Walking down the path that runs parallel to the polished black granite wall that is the heart of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, there exists an angle about half way down where it is hard not to notice that one wing of the wall points directly at the towering Washington Monument, and the other wing points directly at the Lincoln Memorial.

As the descent continues, however, the skyline and buildings of the National Mall fade away and the wall and its patrons become isolated— set off and secluded from their busy metropolitan surroundings.

| A statue that is part of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Nayda Verier-Taylor). |  |

When 20-year-old Yale architecture student Maya Ying Lin conceived the design of the memorial, she had two primary objectives: to make the memorial be about the veterans, their service and their lives and not about politics. She sought to keep the design simple so that everyone would be able to respond and remember. Since its completion in 1982, it has done just that.

Paul Kozek, who has been active in the Navy for 17 years, is one of more than 20 part-time volunteers that give their time talking with and guiding visitors through the memorial—especially the wall.

“In the 18 months that I have worked here, of the three components of the memorial—the wall of names, the Three Servicemen Statue and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial– the one thing that every visitor remarks on is [the wall] and its simplicity. Part of its appeal is certainly its ‘show, don’t tell’ design,” Kozek said.

Today the wall boasts an overwhelming 58,254 names, each one representing a fallen soldier who died between 1961 and 1973. They are positioned in chronological order of date of death, giving each name a defined place in history.

“The names are the essence of the memorial—they dominate everything. At the middle, you feel like you’ve disappeared and are alone with the wall and its names,” Kozek said.

On any given day, people from all walks of life come to visit. Today, a recent graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy has come with some of her classmates to remember those who served before her. A boy of about nine runs up and down the wall trying to locate a name for his school group’s scavenger hunt. When he finally finds it, Kozek helps him make a “rubbing” of the name on a special piece of paper.

|

Visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial take a name “rubbing” as a keepsake of their trip (Photo by Nayda Verier-Taylor). |

Down towards the end of the wall, a little girl places a note to the grandfather she never met at the foot of the wall where his name is etched while her father weeps quietly. The scene is dramatic, but serene.

When the memorial was dedicated 25 years ago, it symbolized a homecoming for many veterans who, although they had returned home many years before, had never received closure under such bittersweet circumstances.

Dr. Scott Fairchild, a retired U.S. Army psychologist and a recognized authority on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), believes that the memorial serves as a path to reconciliation and healing and an end to the controversy and division that clouted the Vietnam War and those who fought in it.

“It honors the service members who gave their lives in one of the most mismanaged misadventures in our history,” Fairchild said. “It is a tribute to [the soldiers’] brothers, a place of contemplation for their friends and family members and it takes on added significance due to the lack of a ‘welcome home’ that they received.”

For Memorial Day weekend 2007, Fairchild—who is the president of Welcome Home Vets, Inc.—will travel to Washington, D.C., to witness more than 15,000 veterans on motorcycles who will cross the Potomac Bridge, two by two to arrive at the memorial.

“As they cross the bridge, there will be a Marine in full uniform, standing in the center of the road, saluting them, with a sign at his feet [that says] ‘Welcome Home’,” Fairchild said.

Each visitor’s connection to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial varies. Originally, it was intended for those who served but, over the last two decades, the memorial has impacted those who have no connection to the Vietnam War whatsoever.

Even for those who are younger and who view Vietnam as a piece of history found only in their high school textbooks, the memorial evokes many emotions.

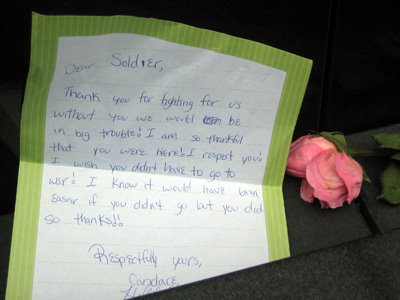

|

A schoolgirl’s note to Vietnam veterans thanking them for their service to their nation (Photo by Nayda Verier-Taylor). |

“Visiting this place always makes people more aware of the impact of war. Especially when our nation finds itself at war once again. It really demonstrates the price of war— a price that is paid in human lives,” Kozek said.

Just as the Vietnam War interrupted life for all Americans, so too does it interrupt the landscape of the National Mall. Just as the war plunged into a seeming abyss of death and terror, so too does the wall as each panel bears more and more names. And finally, just as the war came to an end, the wall symbolically fades up to the other side and rejoins the familiar plane of American life.

“When visitors reach the end of the wall they are left to reflect on what they have seen, as if they have emerged from a deep, somber meditation,” Kozek said. “They haven’t been told what to think or how to feel, nor do they need to be. The names speak for themselves as their fallen owners can no longer speak.”

If You Go

- Hours: Daily, 8 a.m. to midnight (closed on Christmas Day).

- Admission: Free.

- Address: 900 Ohio Dr., SW, Washington, D.C., 20024.

- Phone: 202-426-6841.

- Web site: http://www.nps.gov/vive/.

- Facilities: Bookstore, restrooms, concessions.

- Transport: Accessible via the Foggy Bottom Metro Station.

Comments are Closed