Students view history at Ford’s Theatre

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Dozens of student groups stood in front of Ford’s Theatre on NW Tenth Street in downtown Washington in frigid 40-something degree spring weather just as 1,500 theater-goers did 142 years ago.

As they entered the front doors, some were directed to the seats on the main level, others upstairs to the balcony, climbing the spiral staircases just as people did the night of President Abraham Lincoln’s death.

From the balcony, the visitors had a clear view of the box where Lincoln was shot on April 14, 1865.

|

The exterior of Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site in downtown Washington, D.C., as it appears today in Washington (Photo by Ashley Davidson). |

Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site was filled with strobe-like camera flashes as more than 600 students and adults photographed the president’s box and its surroundings, trying to capture the moment as they relived history.

Merely five days prior to the day Lincoln was assassinated, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered his troops at Appomattox Court House in Virginia and the Civil War came to an end after four years.

“There were fireworks and parades in Washington,” explained National Park Service Ranger Jeremy Zegas during an approximately 30 minute historical lecture for the visitors. “The public was showing its emotion and celebrating the end of the war.”

Zegas explained that two days later, on April 11, President Lincoln stood before a crowd of people and spoke of reconstruction of the South, as well as his belief that African Americans should have the rights of citizenship and to vote.

Zegas explained that two days later, on April 11, President Lincoln stood before a crowd of people and spoke of reconstruction of the South, as well as his belief that African Americans should have the rights of citizenship and to vote.

Standing somewhere among the crowd was prominent actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth who is reported to have said at the time, “Now by God I’ll put him through. That’s the last speech he will ever make.”

And it was.

On April 14, President Lincoln, his wife Mary, and a young officer Henry Rathbone and his fiancé watched “Our American Cousin” from the box.

The president’s visit had been advertised, according to Zegas, adding that it was “much easier to see the president than it is now” prior to the days of 24-hour protection by the Secret Service.

Booth received word and planned his attack. As an actor, he knew both the theater and the play extremely well, so his plan was well orchestrated.

He knew the back entrances and trap doors as well as when the actors would be coming on and off the stage, Vegas explained. During Act 3, scene II, he knew there would be uproarious laughter and no one would ever even hear the gunshot, let alone be looking up at the president’s box.

Booth walked right up the spiral staircase the students had taken just a few minutes earlier, strolled across the back of the balcony where they sat now and entered the box.

“He was an actor that everyone knew, so an actor walking through a theater didn’t seem out of place,” Zegas said. “He showed a sort of business card to the messenger at the door and was allowed to see the president.”

|

The president’s box, where Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, is decorated as it was on the historic night (Photo by Ashley Davidson). |

Right when the crowd began burst into fits of laughter, Booth fired his 0.44-caliber, single-shot derringer.

“An actor on stage said it just sounded like someone backstage dropped a prop. It just sounded like a pop,” Zegas said.

It was not until someone in the audience saw smoke and heard screaming that the rest of the theater knew what had happened.

Zegas explained that Booth had no problem jumping from the box to the stage as part of his escape, a drop of about 12½ feet, because he had acted in plays with various stunt work.

However, his spur became caught in a flag as he fell, breaking his leg, but managed to escape out the back of the theater on his horse that a stagehand had been watching.

While Booth did escape, he was captured a few days later in Virginia 80 miles from the theater, Zegas said.

A 23-year-old doctor only six weeks out of medical school responded to the gunshot and explained it was fatal, according to Zegas.

|

The front sitting room of Petersen House, across the street from Ford’s Theatre (Photo by Ashley Davidson). |

Lincoln was transported across NW Tenth Street to the Petersen boarding house, where he died at 7:22 a.m. the next day at the age of 56.

“The theater was shut down immediately [after the assassination] and guards were posted there 24/7,” Zegas said.

In 1866, the U.S. government purchased the theater, using it as an office building for the next 90 years.

“It was reopened [as a working theater] in 1968. The front façade is original and the interior was rebuilt based on evidence and photos,” Zegas said.

While the stage is a “bit larger,” he explained, there are various items that are original, including the photograph of George Washington that still hangs in front of the box just as it had the night of Lincoln’s death.

“The red loveseat [in the box] is original and there is a wooden chair that is original to one of the boxes, but we’re not sure if it was that one,” he said.

After the lecture, the student visitors traveled downstairs to the basement and the Lincoln Museum, which holds many items from Lincoln’s time, his life and the night of his death. The displays include floor tiles, playbills, tickets, the clothes Lincoln wore when he was shot, and pieces of rope used to hang the Lincoln conspirators.

The government purchased many of the items from the personal collection of Osborn Oldroyd, a collector of Lincoln memorabilia, in 1926 for $50,000.

| Students line up to enter Petersen House (Photo by Ashley Davidson). |  |

With its reopening in 1968, Ford’s Theatre became a working theater once again.

“A full effort began in the late 1940s,” explained Ranger Lauren Gurniewicz, who has been with the theater for about 2½ years. “Lincoln had been at Ford’s Theatre at least a dozen documented times, but there could have been more that we don’t know about and he probably went to other theaters as well. It’s an important part of Lincoln’s story.”

Gurniewicz said she thinks the renovations to Ford’s Theatre had done justice to what it was like in Lincoln’s time.

“The experience is as close as we could get it. Of course there are some things, like we can’t fit as many people because of fire code regulations and much of the lighting is in the balcony,” she said. “It’s so different than a modern theater.”

Approximately 24 million people from around the world visit Ford’s Theatre each year.

Ford’s Theatre performs plays, putting on a comedy, the holiday classic A Christmas Carol, a drama, and a musical every season, Gurniewicz said.

Meet John Doe, a play based on Frank Capra’s film, is currently playing through April 29, 2007.

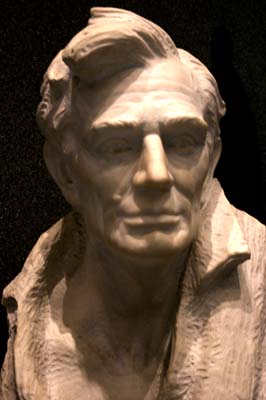

| At right, the museum displays items from the assassination. Below, a sculpture of Abraham Lincoln is displayed (Photos by Ashley Davidson). |  |

One Destiny, a single-scene, 45-minute play about the assassination of Lincoln, runs until May 12, 2007.

Gurniewicz explained that most of the theater’s plays are contemporary, but some are from Lincoln’s era.

“We have a wide variety,” she said, adding that the theater performed Shenandoah, from the Civil War time. “The productions tell the American story.”

Gurniewicz said Ford’s Theatre celebrates Lincoln’s love of the theater.

“It’s a place to come to honor and remember the legacy of Lincoln,” Zegas said.

If You Go:

511 NW 10th St., Washington, D.C. 20004.

511 NW 10th St., Washington, D.C. 20004.- Daily, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., except Dec. 25. Call ahead. The theater often closes early for rehearsals.

- Parking is limited. Private paid parking garages and lots are located downtown north of the National Mall. Free on-street parking is limited. There is limited free day-long parking at Ohio Drive SW (along the Potomac River south of the Lincoln Memorial) or in Lots A, B & C south and west of the Jefferson Memorial.

- Elevators will be available beginning in May 2007. There is a book with some museum items for those who can not access the downstairs museum.

- Box office: 202-347-4833. National Park Service on site: 202-426-6924.

- http://www.nps.gov/foth.

- http://www.fordstheatre.com.

Comments are Closed